1890s Biblical Pinback Buttons by Whitehead & Hoag Co.

Religion: Christianity

Time Period: 1890s

Type Of Garment:

Tags: Children, Evangelical Protestantism, Evangelism, Everyday, Jesus, Nicodemus, , Sunday School, United States, Whitehead & Hoag

The Creator:

For decades Whitehead & Hoag Co., founded in 1892 by Chester R. Hoag and Benjamin S. Whitehead, was the patent holder (1896) and preeminent manufacturer of the pinback button—a slightly bigger than a dime-sized pin that could be worn on one’s lapel or collar. While they also made small medals, ribbon badges, and other advertising novelties, the pinback button became their most popular product. It revolutionized advertising and became a popular way to promote sales, as well as various causes, from suffrage to presidential campaigns (Newark’s Attic 2015; Hake n.d.; Mazur 2022). With their ability to convey a message quickly through a combination of graphics and minimal text, the pinback button functioned as an early form of wearable messaging, similar to how social media posts and branded clothing function today (Carter 2021).

Whitehead & Hoag’s political and civic buttons dominate the online landscape and scholarly investigations today, but the company also made Christian buttons, including ones promoting scriptural texts, “church going” campaigns, the Catholic Discussion Club, and a variety of biblical scenes (see Figure 1). While Whitehead was a Methodist and Hoag a Presbyterian, their Protestant affiliation did not prevent them from creating Catholic buttons, in a similar way they refused to let personal political leanings interfere with making buttons for different political party candidates. Business and sales trumped personal allegiances, resulting in a catalog of Christian buttons that crossed denominational boundaries. This pragmatic approach positioned the company to serve the growing market for religious educational materials, particularly those supporting the Sunday School movement.

The Object:

It is unknown how many Christian buttons Whitehead & Hoag made as records for the company were destroyed when the business closed in 1959. Currently, I have thirteen different biblically-themed pinback buttons by Whitehead & Hoag, Co. that I purchased over twenty-five years ago at a flea market in Raleigh, North Carolina. Of the thirteen, two feature floral decorative elements and biblical passages, two focus on David (David and Goliath, David and Solomon), six depict moments in the life of Jesus, and three portray events in the life of Paul (see Figure 2). Each button bears a short caption to avoid any confusion about the events shown. While this does not represent a complete collection, based on online research, this is a sizable sample. In this entry, I will focus on one representative example from the life of Jesus.

The Jesus-focused buttons emphasize central moments in his life and ministry—his nativity, his blessing of the little children, the Last Supper, the Crucifixion, and the Ascension. See Figure 3. Additional examples found online include The Transfiguration and Jesus Calming the Sea. These scenes and stories regularly appeared in children’s Sunday School curricula of the period (Boylan 1988: 40). In an era of greater biblical literacy, these pivotal events would have been familiar and recognizable to children and other viewers, making them ideal for pinback buttons.

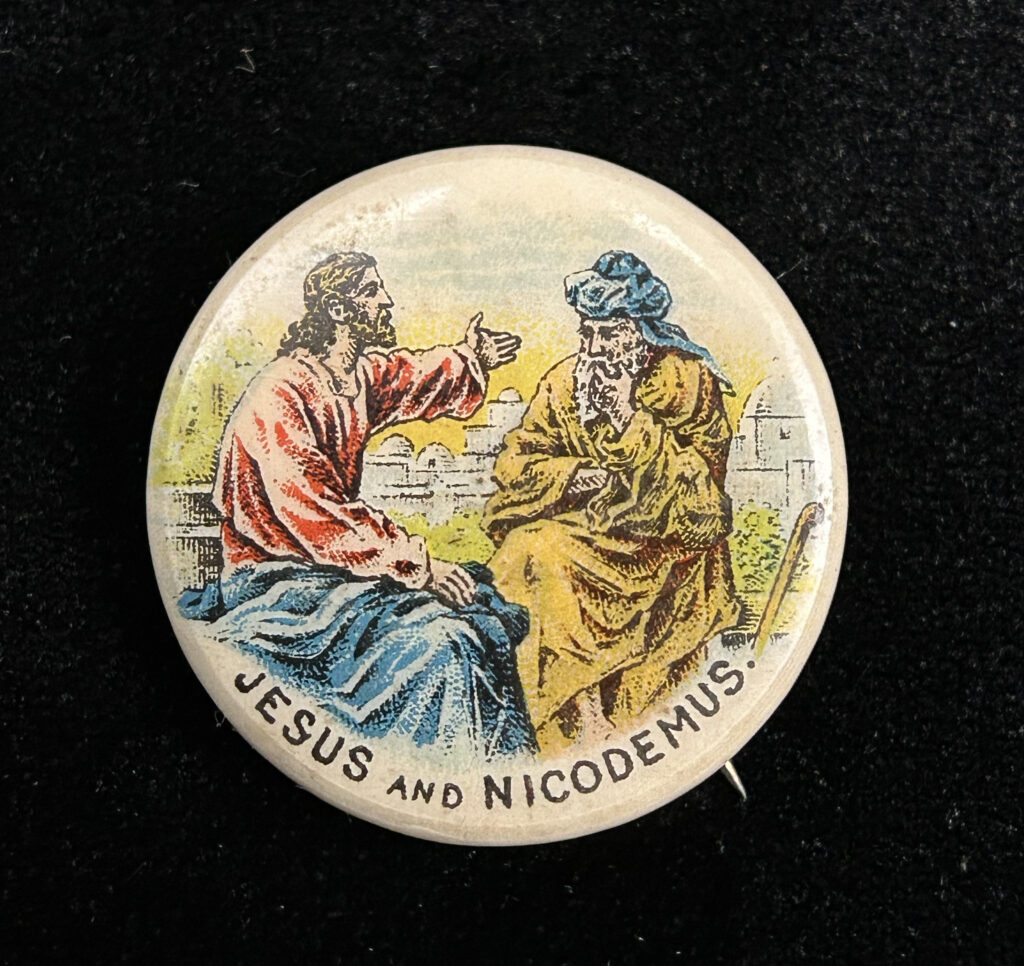

However, one button captioned “Jesus and Nicodemus” stands out as it deviates from this pattern of well-known iconographic biblical scenes. Recorded in the Gospel of John, Chapter 3, this conversation is not usually on par with other pivotal moments—nativity, crucifixion, ascension—in Jesus’ life. Nor is it a biblical scene with a standard recognizable iconography. The only way a viewer would know what is happening in the scene is through the caption. Thus, the making of this button and its inclusion in the collection seems significant for understanding the evangelical Protestant context of these materials.

The artwork of the button resembles that of others and Sunday School materials from the time. As scholar Colleen McDannell explains, Protestant companies at this time created “brand recognition” by using “only a limited number of images” by artists, including Bernard Plockhorst, Henrich Hofmann, and Warner Sallman (McDannell 2018: 486). The artwork on the Whitehead & Hoag buttons is in keeping with this artistic style.

The brown-haired bearded Jesus appears seated on the left wearing red and blue robes, while the older Nicodemus sits on the right in yellow robes and a blue turban (see Figure 4). The inclusion of some greenery suggests they are seated in a garden with a town or small city behind them. More important is the body language of the two figures. Jesus looks directly at Nicodemus and leans toward him with his left arm reaching out in a gesture that suggests an invitation, a plea for him to understand. Nicodemus, in contrast, sits with his gaze directed downward. His head rests on his left hand while he holds his right arm close to his chest. The pose suggests a thoughtful, yet cautious, listening mode. The button includes nothing else beyond the caption; it leaves it to the wearer/viewer to fill-in the rest of the story and discern the lesson being taught and remembered. It is a lesson that identifies these buttons as part of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century evangelical Protestantism.

In John 3, the Pharisee Nicodemus, moved by the miracles performed by Jesus, comes to him under the cloak of night to ask questions and learn more about his teachings. Jesus responds, in verse 3, “except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.” A confused Nicodemus, who has interpreted this imperative literally, asks how such a thing is possible. Jesus then emphasizes that this rebirth is spiritual and restates in verse 7, “ye must be born again.” The conversation culminates in verse 16, with what would become one of evangelical Protestantism’s most quoted passages: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.”

The Context:

The dialogue between Jesus and Nicodemus took on particular significance in the history of evangelical Protestantism, which emphasized the theological importance of being “born again” as essential to salvation. John 3:16 served as a concise faith statement that evangelical Protestants widely used in their missionary outreach. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Sunday School movement became one of the primary vehicles for this evangelistic goal. While the idea originated in England and revolved around teaching the rural poor to read and grow in faith through Sunday schooling, the movement was transformed in the American context. By the 1830s Protestants had refocused the interdenominational Sunday School movement around the evangelism and conversion of children (Glass 2018; see also Boylan 1988). As a result, the market for appropriate Christian literature and materials for children and youth expanded and new products emerged.

One of the early and popular purveyors of these materials was David C. Cook, a leader in the American Sunday School movement whose eponymous company published nondenominational Sunday School materials. Companies like Cook and others offered diverse Protestant Christian products. “Teachers could buy cradle rolls (for enrolling babies), maps, art equipment, record books, diplomas, wall rolls of biblical scenes, and puzzles to help them socialize children into a religious world” (McDannell 2014; 486). This range of products highlights how evangelical Protestants sought to use consumer goods as a way to foster Christian values and beliefs in children.

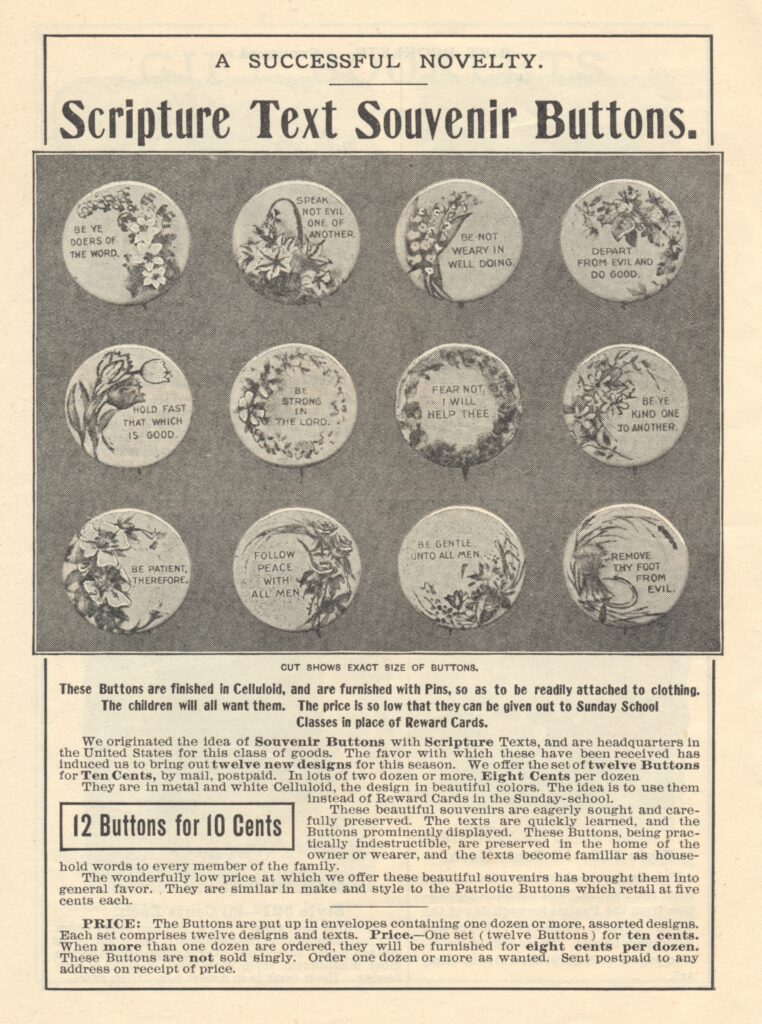

An examination of an early 1900s “Children’s Day Supplies” catalog from David C. Cook highlights some of these products. The catalog promotes “Sunday School Medals,” coin-like medals featuring a biblical scene on one side with typically a verse on the back. Other products include “Children’s Day Exercises,” room decorations, and gift booklets. The last page of the catalog includes an advertisement for a group of twelve pinback buttons (see Figure 5). These buttons feature floral motifs and short Bible verses, similar to those made by Whitehead & Hoag. The ad also helpfully explains what to do with them. It urges Sunday School teachers to “use them instead of Reward Cards,” and states that “these beautiful souvenirs are eagerly sought and carefully preserved. The texts are quickly learned, and the Buttons prominently displayed.” The advertisement assures potential buyers that as the buttons are worn “the texts become familiar as household words to every member of the family” (David C. Cook).

This advertisement provides helpful context for understanding the purpose of the Whitehead & Hoag buttons. Whether made by Whitehead & Hoag, David C. Cook, or another company, the buttons are intended to serve multiple functions for the child wearer. They reward children for attending Sunday School and learning Bible verses. Then by wearing the buttons, the children maintain and reinforce their Christian identity—making their Christian commitments public and visible. And, as the ad states, they also, at least ideally, encourage others to learn and ponder the scriptural lesson on the button thereby fulfilling an evangelistic function. These functions all serve to reinforce important values and practices within evangelical Protestantism—the centrality of the Bible, the public proclamation of faith, and the emphasis on evangelism.

Interestingly, one button in my collection features a pastel floral wreath bearing the words “Have Peace with One Another,” part of the biblical verse found in Mark 9:50. The identifying information on the back of the button lists both “David C. Cook Publishing, Publisher of Sunday School Requisites” and “Whitehead & Hoag” (see Figures 6 and 7). We know, then, that David C. Cook, and likely other similar companies, hired Whitehead & Hoag, Co. to create buttons as part of the many products that supported the Sunday School movement.

In this analysis, we can see how a seemingly simple pinback button, smaller than a quarter, served as a powerful material object that infused Protestant doctrine and practice into everyday life. Through the combination of recognizable art and minimal text, pinback buttons transformed biblical stories and abstract theology into tangible objects that children could possess, display, and use to express their identity. Further, as a wearable object—part of the realm of clothing and fashion—the pinback button provided evangelical Protestants with an innovative way to make their religious messages portable and visible in public spaces. This trend of using available technology and media to spread its Christian message has been and continues to be a hallmark of evangelical Protestantism today, as seen in Christian-themed bumper stickers, cell phone cases, and especially T-shirts.

Lynn S. Neal, Professor of Religious Studies, Wake Forest University

26 February 2025

Tags: Children, Evangelical Protestantism, Evangelism, Everyday, Jesus, Nicodemus, Pinback Button, Sunday School, United States, Whitehead & Hoag

References:

Boylan, Anne M. 1988. Sunday School: The Formation of an American Institution, 1790–1880. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Carter, Christen. 2021. “Message in a Button.” JSTOR Daily, 6 December. Available at: https://daily.jstor.org/message-in-a-button/.

Cook, David C. n.d. Children’s Day Supplies. Chicago: David C. Cook Publishing Company.

Glass, Matthew. 2018. “Sunday School Movement.” In Encyclopedia of American Religious History, edited by Edward L. Queen II, Stephen R. Prothero, and Gardiner H. Shattuck Jr., 4th ed. Facts On File. https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6ODM3MTg3?aid=107358.

Hake, Ted. n.d. “Whitehead & Hoag Company History.” TedHake.com. Accessed 24 February 2025. Available at: https://www.tedhake.com/viewuserdefinedpage.aspx?pn=whco.

Mazur, Eric. 2022. “Strange Bedfellows? Technology, Campaign Finance, and the Marketing of Religion on U.S. Presidential Campaign Buttons.” Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 11: 103–138. https://doi.org/10.1163/21659214-BJA10066.

McDannell, Colleen. 2014. “Christian Retailing.” In Religion and American Cultures: Tradition, Diversity, and Popular Expression, edited by Gary Laderman and Luis León. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. Accessed February 24, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Newark’s Attic. 2015. “The Whitehead and Hoag Company, 1892–1959.” Newark’s Attic, August 26. Available at: https://newarksattic.blog/2015/08/26/the-whitehead-and-hoag-company-1892-1959/comment-page-1/.