1976 Jewish Prayer Shawl

Religion: Judaism

Time Period: 1970s

Type Of Garment: Prayer Shawl

Tags: , , feminism, Judaism, prayer shawl, Ritual, tallit, United States

Object:

“You’re my companion.” “You’re always with me.” “Everything else might be taken away, but not you.” So went the lyrics to a popular Yiddish love song that made the rounds of the American Jewish community’s recording studios, theatres and family pianos in the aftermath of World War I. Its object of devotion, though, was not a person, as one might expect, but a garment – and not an everyday garment, at that, but a sacramental one worn by male Jewish worshippers while at weekday and Sabbath morning prayer services.

Encircling the upper half of the body in a large swath of cream-colored wool or silk accentuated by a series of bold inky stripes, four sets of dangling fringes at each end and an embroidered collar, this physical iteration of “God’s embrace” was known in Hebrew as a tallis,or, in today’s modern pronunciation, as a tallit. (see Figure 1.) The song, drawing on the affectionate Yiddish diminutive, called it a talesl (a little tallis).

Heralded for its constancy, the beloved ritual item was also recognized as a hallmark of distinctiveness. Much like a flag and often as generously proportioned as one, the tallit, whose origins date back to the Hebrew Bible, symbolized Judaism to the world outside of its precincts. In illustrated manuscripts and oil paintings (see Figure 2), as well as in Christian publications on Jewish rituals, its properties visually denoted the wearer as a person of the Jewish faith.

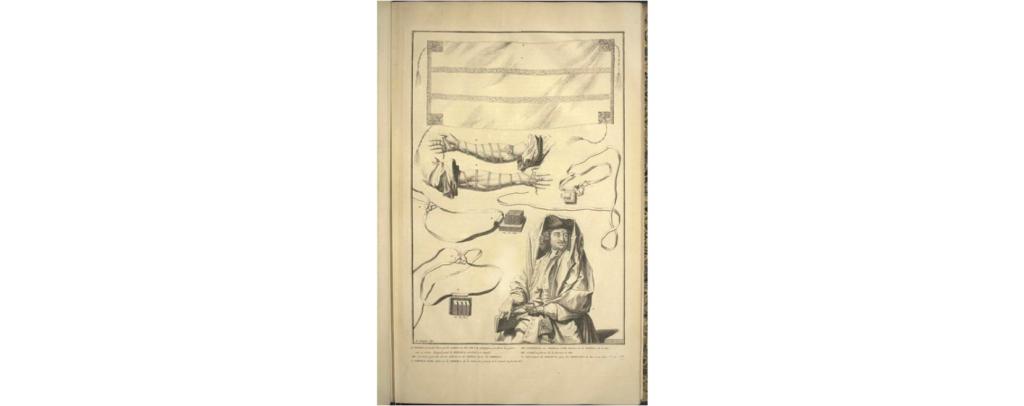

When, in the mid-18th century, Bernard Picart and Jean-Frederic Bernard published Religious Ceremonies of the World, their path-breaking, multi-volume, and generously-minded narrative of the world’s “customs and ceremonies…intersper’d with the most agreeable Particulars,” they accompanied their description of the prayer shawl with an etching of a Jewish man wearing one, as you can see in Figure 3 (Joselit 2010).

and Jean-Frederic’s Religious Ceremonies of the World, 1723. Public domain.

Creator:

At once a curiosity and a sacred object, the tallit worn by Ashkenazic or western Jews bore the imprint of a man-made commodity. (The ritual garb worn by Mizrachi or eastern Jews is an entirely different story and lies outside the purview of this article.) Once woven by hand by skilled male artisans, the garment developed into a factory-produced item by the late 19th century, its manufacture helping to fuel the economy of towns such as Kalusyn, Poland, in the Old World and Paterson, New Jersey, in the New. Later still, a tallit made in Israel and purchased on a visit to the Holy Land–a souvenir with added punch—became de rigueur.

In pre-modern times, the tallit would first be purchased from a local artisan and then passed down from one generation to the next. In the modern world, especially in America, stores that carried religious articles – prayerbooks, rabbinic commentaries, and ritual objects – became its main, and often sole, purveyors (see Figure 4). Advertising a specially priced “bar mitzvah set” as an inducement, an incentive to shop, a prayer shawl was made available to consumers in its own velvet bag, along with a pair of tefillin or phylacteries in a matching, if smaller, container: a gift item for thirteen-year-old boys on the eve of the ritual ceremony that marked their coming of age and with it, the launching of their tallit-wearing lives (see Figure 5).

Modernization affected not only the process by which the tallit was produced and circulated but its size and fabrication as well. From a piece of cloth so capacious that, when unfurled, it covered much of the upper body, its outer edges nearly reaching the floor, the modern prayer shawl dramatically shrunk. More of an ornament than a presence – more scarf than stole – it now hung limply, unobtrusively around the neck. What’s more, the modern tallit was increasingly fashioned out of washable synthetic fabrics rather than the hard-to-keep-clean wool and silk of yesteryear. Its practicality a plus, the polyester version was heralded as proof of the age-old garment’s stability, an acknowledgement of its enduring appeal even in the fast-paced modern world. As Ziontalis, one of America’s leading manufacturers and distributors of Jewish prayer shawls, liked to say, its product combined the “essentials of our age-old heritage with the esthetics of contemporary good taste” (Ziontalis n.d.).

For decades, the synthetic tallit reigned supreme – and in some quarters, still does. But these days, its fuller, more traditional counterpart has experienced a comeback among some younger worshippers who, in search of authenticity, have made a point of donning one. The traditional tallit also remains the article of choice among contemporary Hasidic and ultra-orthodox Jews who, unlike their more liberal coreligionists, tightly held onto it even as the slimmer model became the norm – or, who, as was the case among Reform Jews, abandoned it altogether on the grounds that it was unduly “oriental,” by which they meant both non-Western and decidedly old fashioned.

Wearer and Reception:

Of all the changes the garment has endured, none was greater or had more of a far-reaching impact than the radical shift in those who, increasingly, wrapped one around their shoulders: American Jewish women. Inspired by the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, calls for their greater integration within the Jewish ritual economy as well as their training and credentializing as rabbis reverberated loudly within their ranks. Before long, adolescent Jewish girls and their mothers claimed the tallit as their own, along with many of the religious obligations formerly incumbent only on their fathers and sons. No longer was the prayer shawl the exclusive property of the men in the family.

Energized by the prospect of religious equality and a willingness to assume the same religious responsibilities as men, some American Jewish women took on and understood the wearing of a tallit as a religious injunction: they had to. Others preferred to think of the practice as a matter of choice: they wanted to. They liked the way it made them feel. In dozens of feature articles in synagogue newsletters and in Jewish feminist publications such as Lilith, a quarterly magazine “exploring the world of the Jewish woman” since 1976, female tallit-wearers gave voice and bore witness to its emotional resonance. “It felt right,” recalled one woman who began wearing one in 1976. “I savored the feeling of being embraced by God’s Presence.” When I don’t put it on, she added, “I feel something is missing; I feel bereft” (Sohn 1994).

Not all Jewish women, though, took to the tallit. Some felt uncomfortable with the distinction between having to and wanting to, between imperative and volition, uncertain of what side of that equation to situate themselves. Others found it difficult to shake off the age-old notion of the tallit as a male garment and couldn’t quite see themselves in one. “Old habits die hard,” explained a female synagogue-goer of her reluctance to possess a tallit of her own (Williams 1994). Still others were constrained by strong opposition to the new-fangled practice within their own families. At first, many American Jews at the grass roots, including parents and spouses, did not take kindly to the sight of their tallit-clad womenfolk, much less their ascension into the ranks of the rabbinate. Both phenomena, their critics insisted, ran counter to, and undermined, normative Jewish ritual and practice – and could not be countenanced.

All the same, growing numbers of women warmed to the tallit. Some wrapped the prayer shawl of a deceased grandfather around their shoulders. Lest the yellowing fabric molder in a drawer or on the back shelf of a closet, they reclaimed it, giving it a new lease on life, aligning past and present. Others drew on the era’s parallel reclamation of needlework as a feminist statement by putting the stamp of their own personality on the prayer shawl and making it their own. Transforming a somber garment into a fanciful one, they added a touch of lace here, a smattering of hand-embroidered flowers there; silk-screened family photographs onto its expanse of fabric or created a pattern of stripes by making use of a father’s discarded neckties. Soon enough, the feminized tallit became commercialized, ready-made versions fashioned out of organza and pastel-colored silk increasingly available in the marketplace or online.

Sheer Organiza Tallit,” sold by The Tallis Lady.

For tallit-clad women, writes Rabbi Susan Schnur and her daughter Anna Schnur-Fishman, drawing on a cluster of resonant verbs, this ritual garment “caressed, cloaked, enfolded, hugged, cradled, cushioned, loved, sheltered, swaddled, embosomed, fondled, nestled, shielded, sheltered, protected, comforted, enveloped, and enshrouded them” (Schnur and Schnur-Fishman 2006).

Once it became clear that the tallit and the faith it represented would not collapse under the dual weight of ornamentation and individuality, it didn’t take long before those worn by men also evolved into more of a personal statement than a uniform, standardized one (see Figure 8). These days, in what constitutes a remarkable about-face, idiosyncratic prayer shawls far outnumber their traditionally restrained counterparts within liberal, progressive Jewish circles– a testament to the ritual garment and Judaism’s mutual adaptability.

Shalomi, who originated it, ca. 1983. Photo Courtesy of the Jewish Museum Vienna, inv. no. 26495; Photo Credit: Lukas Pichelmann. Used with Permission.

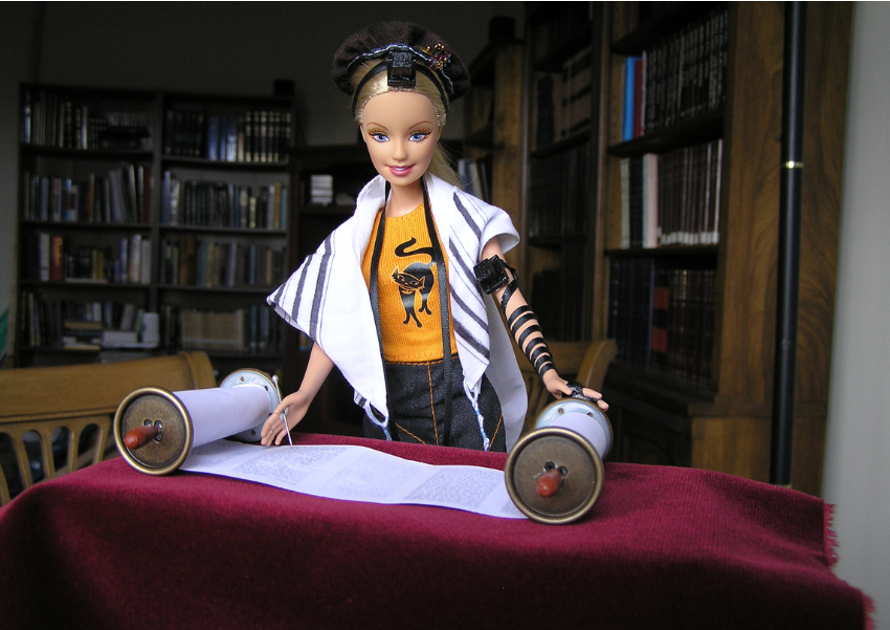

And yet, perhaps the most striking example of the age-old faith’s resilience can be found not in the pews of the sanctuary but in the realm of popular culture: Amid a sea of Barbies dressed fashionably and professionally, one can find Barbie wrapped in a tallit (Namerow 2006).

Jenna Weissman Joselit is the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University. Her latest book, Mordecai M. Kaplan: Restless Soul, will be published in March 2026 by Yale University Press as part of its “Jewish Lives” series.

10 December 2025

TAGS: Judaism, United States, bar mitzvah, feminism, Barbie, prayer shawl, tallit, ritual

References:

Joselit, Jenna Weissman. “Enlightened Views,” Tablet, July 1, 2010, https://www.tabletmag.com>arts>letters>articles>enlightened views

Namerow, Jordan. “Barbie Wears a Tallit?!” Jewish Women’s Archive, November 8, 2006. Available at https://jwa.org>blog>barbietalit

Perlmutter, Arnold and Wohl, Herman (music); words by Solomon Small (Shulewitz). Dos Talesl. Available at https://youtu.be/lQgvr0KAJ30?si=mG9FQWOqY3kTxm_r

Personal interviews 2025. Author’s in-person interview with Rabbi Joanna Samuels, September 8, 2025; author’s phone interview with Rabbi Jane Kanarek, November 25, 2025.

Schnur, Susan and Anna Schnur-Fishman. “How Do Women Define the Sacred?” Lilith, Fall 2006. Available at https://lilith.org/articles-how-do-women-define-the-sacred/

Sohn, Ruth. “Tallit for Women,” Minyan Monthly, 8.1, October-November 1994

Williams, Sharon L. “Another View on Tallit for Women,” Minyan Monthly, 8.2,December 1994

“Four Reasons to Ask for a Ziontalis,” n.d. Available at https://www.ziontalis.com under “About Us.”