1961 Buddha Brooches by Joseph J. Mazer Co.

Religion: Buddhism

Time Period: 1960s

Type Of Garment: Brooch

Tags: brooch, Buddha, costume jewelry, Everyday, Mazer, spirituality, United States

The Creator and Object:

While costume jewelry is not uniquely American, it has flourished in the American context. As one scholar observes, “Costume jewelry, in itself a replaceable ornament and an expression of creativity and inner beauty rather than a symbol of material wealth, is well suited to a consumer-conscious society in which objects are meant to be disposable, following the American creed, ‘Buy new, discard the old’” (Cera 1992: 149). Having survived the scarcity of supplies during the World War II years, costume jewelry became a popular jewelry choice with some manufacturers continuing to imitate the designs and styles of fine jewelers, while others embraced their “fabulous fakes” (Cera 1992: 186).The Joseph J. Mazer Company (trademark Jomaz), founded in the 1940s after branching off from the earlier Mazer Brothers jewelry, represented the former trend.

The company was part of the vibrant costume jewelry scene alongside companies, such as Napier, Monet, and Trifari. With a showroom on West 36th Street in New York City, consumers enjoyed Mazer’s elaborate jewelry forms, which ranged from animals to flowers to abstract shapes, adorned with brilliant rhinestones and colored glass. According to one collecting site, in the early 1960s, Mazer’s style became bolder and more vibrant. “Large, colorful cabochons imitating coral and Persian turquoise along with faceted glass stones mimicking rubies, sapphires, and emeralds were incorporated into many designs crafted of gold-plated metal” (Siegel; see also Ball 1990: 101-107).

At this time, J.J. Mazer’s jewelry also celebrated more Asian-inspired designs. For example, in 1960 Mazer produced the “Maharanee” collection, which highlighted Indian aesthetics. Described as having a “Moghul” style, the jewelry featured intricately worked gold-plated designs with large faux rubies. This collection, though, as well as many others by Mazer did not include religious symbols or figures.

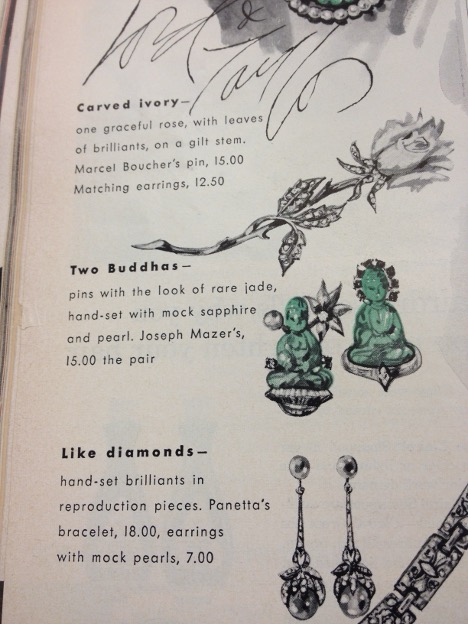

This changed in 1961 when Mazer created a series of Buddha brooches, examples of which can be seen in the advertisement above (see Figure 1). The pair sold for $15.00, the equivalent of approximately $155 in 2025—cheaper than designer jewelry, yet still an investment when the median weekly family income was $110. Both designs are about the size of quarter and feature a gold plate base, faux gemstones, and green glass with “the look of rare jade” molded in the shape of the enlightened Siddhartha Gautama, known as Shakyamuni Buddha (see Figure 2). He is in a meditative pose as indicated by his lotus position and clasped hands. The ushnisha or cranial bump on the top of his head and his stylized curls indicate that he has achieved the state of enlightenment (Brown 2004, 79-82). The brooch on the left features two faux rhinestones on either side of the meditating Buddha (some versions may have featured faux sapphires as mentioned in the advertisement), a faux pearl to the left his head and a lotus flower with a rhinestone center to the right. In Buddhism, the lotus symbolizes transcendence and purity. The flower emerges from the mud yet remains unsullied by its origins. As one scholar writes, “the lotus is a natural symbol for rising above the world” and in relation to the Buddha it highlights how he “lives within the world but is not affected by it” (Brereton 1987, 5519). The brooch on the right highlights the special status attained by Shakyamuni Buddha through a halo made of rhinestones.

Another similar brooch from Joseph J. Mazer not seen in the advertisement exhibits a more elaborate setting. In this design, the green meditating Buddha (almost identical to the one seen in Figure 2) sits on a more elaborate gold-plated base that resembles a lotus flower. Three petals, each featuring a faux amethyst, emerge from the foundation, which resides on three large rhinestones. Two smaller rhinestones appear on each side of the Buddha’s head and a large faux pearl adorns the top of his head, perhaps a reference to or representation of his cranial bump (see Figure 3). Compared to the advertised pins, this example appears more expensive and opulent.

In conducting this research, I also found two other brooches that resemble those by J.J. Mazer, but do not bear the Jomax trademark or any other maker marks. This suggests that Mazer either made unsigned variations of the brooches or other jewelry competitors copied it (see Figure 4). The first of these imitates the brooch seen in Figure 2 almost exactly, while the other features a meditating Buddha made from molded green glass with three rhinestones—one below the base and one on either side of the Buddha. Interestingly, in this design, the Buddha is shaded by a parasol, a symbol of royalty, as well as physical and spiritual protection (O’Brien 2019). One can see a few other 1960s brooches featuring Shakyamuni Buddha on auction sites, including Ebay and Etsy. The existence of these imitations indicates the existence of a trend and a certain level of popularity for such designs.

The Wearers:

What we do not know about the brooches is who bought and wore them or how they viewed this fusion of Buddhism and costume jewelry. Did they know the symbolic spiritual meanings about cranial bumps and lotus flowers encoded in the designs? Or did consumers see them simply as exotic and popular accessories that gave its wearer a sense of cosmopolitan panache? As art pieces, the brooches exude a quiet, understated elegance given their size and color. Yet the subject matter—the Buddha—simultaneously infuses the pieces with an international, worldly flair. Perhaps, for consumers in the 1960s, the details of Buddhist symbols mattered less than the meaning of the piece as a whole and the “Asian spirituality” it represented.

The Context:

Sociologist of religion Robert Wuthnow describes how American religion shifted in the 1960s from a “dwelling” mode to a “seeking” one. He chronicles how this new “spirituality of seeking emphasizes negotiation: individuals search for sacred moments that reinforce their conviction that the divine exists, but these moments are fleeting; rather than knowing the territory, people explore new spiritual vistas, and they may have to negotiate among complex and confusing meanings of spirituality” (Wuthnow 1998: 4). Amidst this changing religious landscape, Asian arts and religions became increasingly popular.

Several factors contributed to this interest in Asian spirituality. For example, after World War II, American GIs brought knowledge of Asian art, culture, and religion back to the United States, which helped increase its popularity (see Fang 2021). On the religious scene, Asian religious leaders, including Swami Prabhupada (International Society of Krishna Consciousness), Reverend Sun Myung Moon (Unification movement), and the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (Transcendental Meditation) gained both notoriety and popularity, especially when the latter mentored the Beatles. Further, in 1965 immigration law changes opened the American borders to people from Asia. As the American religious landscape shifted in the 1960s, American ideas about and interpretations of Asian spirituality became increasingly fashionable.

In many ways, then, Mazer’s Buddha brooches aligned with the popularity of Asian art and spirituality in the 1960s. Interestingly, though, while other jewelry designers embraced a more general “Indian” aesthetic (Becker 1992: 323), Mazer utilized an explicitly religious one. Perhaps this, too, was simply an aesthetic choice. Or maybe it was a prescient one that signaled the religious shifts to come.

Lynn S. Neal, Professor of Religious Studies, Wake Forest University

10 February 2025

Tags: Brooch, Buddha, Costume Jewelry, Everyday, Mazer, Spirituality, United States

References:

Ball, Joanne Dubbs. 1990. Costume Jewelers: The Golden Age of Design. West Chester, PA: Schiffer Publishing.

Brereton, Joel P. 2005. “Lotus.” In Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd ed., edited by Lindsay Jones, 5518-5520. Vol. 8. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA. Gale eBooks. Accessed January 24, 2025. Available at: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=nclivewfuy&id=GALE%7CCX3424501864&v=2.1&it=r&sid=bookmark-GVRL&asid=a4de4df6

Brown, Robert L. 2004. “Buddha Images.” In Encyclopedia of Buddhism, edited by Robert E. Buswell, Jr., 79-82. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA. Gale eBooks. Accessed January 24, 2025. Available at: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=nclivewfuy&id=GALE%7CCX3402600073&v=2.1&it=r&sid=bookmark-GVRL&asid=826fa9ff

Fang, Karen. 2021. “Commercial Design and Midcentury Asian American Art: The Greeting Cards of Tyrus Wong.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7 (1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11548.

“Mazer/Jomaz.” CollectingCostumeJewelry101.com. Accessed January 15, 2025.

O’Brien, Barbara. 2019. “The Eight Auspicious Symbols of Buddhism.” Learn Religions, January 14. Accessed January 15, 2025. Available at: https://www.learnreligions.com/the-eight-auspicious-symbols-of-buddhism-449989.

Siegel, Pamela Wiggins. “The Sparkling History of Jomaz Costume Jewelry.” Antique Trader. Accessed January 24, 2025. Available at: https://www.antiquetrader.com/collectibles/jomaz-jewelry-beauty-beyond-mazer.

Wuthnow, Robert. 1998. After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s. Berkeley: University of California Press.