1965-1966 The Trigère Cult

Religion: NRMs

Time Period: 1960s

Type Of Garment: Coat, Dress

Tags: Cult Following, Cult Stereotype, Fashion Advertising, Fashion Journalism, NRMs, Pauline Trigère

Context:

In the 1960s, new forms of religion and spirituality became popular, including the Children of God, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, Transcendental Meditation, and the Unification movement. Concerned about the popularity of these movements with youth and their deviance from mainstream Christianity, the media and many Americans labeled these groups “cults” (see Bromley and Cowan 2023). This term questioned leaders’ authenticity, recruitment tactics, unconventional beliefs, and religious legitimacy. In the 1970s, these concerns became concretized in the “cult stereotype” as the “cult scare” dominated the American scene (Dillon & Richardson 1994).

As the word “cult” was accumulating its stereotypical meanings in the 1960s, reporters also started using it in fashion discourse. A few employed the word to denote competing fashion trends. One reporter, for instance, noted the “tempest brewing” between “the cults of the beltless and the belted,” while another contrasted the fashions of “Mod madness” with those of the “Elegant cult” (Kelly 1965, Ridings 1965). Other usages denoted the emergence of popular fashion trends. For example, the AP reported that “many of the designers have joined the baby cult with ruffled pinafore, Peter Pan collars and smocking” (“Era of Coy Flirtation Returns with New Fashions” 1965, see also Carter 1965). Similarly, another described the “Little Girl Cult,” that promoted a “baby doll” look with “thigh-high hemlines, chest-high waistlines, booties and bonnets which tie under the chin” (Walker 1965). The media’s cult language highlighted emerging and competing fashion trends. It played into readers’ knowledge of the cult stereotype but did not mention any specific features of it or allude to its religious associations. However, in 1965, Franco-American designer Pauline Trigère (1908-2002) (see Figure 4) launched an ad campaign that utilized the word “cult” to promote her designs and blurred these boundaries.

Object

While Trigère designs were popular and well known, appearing in department store advertisements and fashion photo shoots, the brand did not often advertise in Vogue. This makes the three full-page Trigère ads in Vogue (1965-1966) notable. Further, the ads appear in September and February issues focusing on new fashion collections and American designers. Also, the ads appear early in each issue, maximizing their visibility.

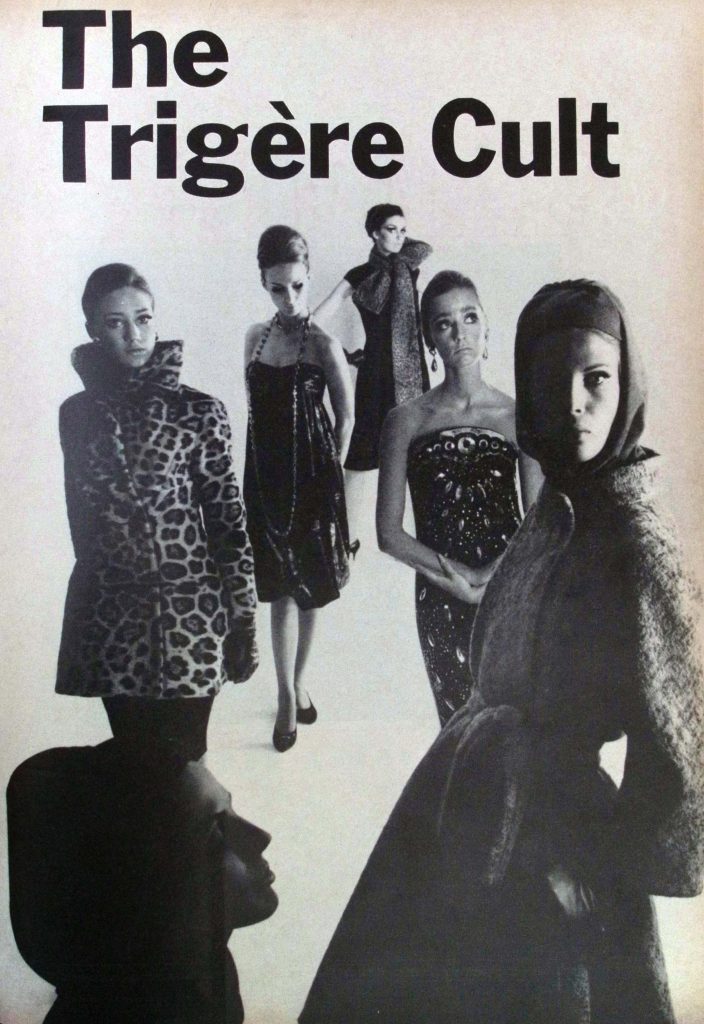

Each ad features only three words: “The Trigère Cult.” The first advertisement includes six models, each wearing a different Trigère design (see Figure 1). Yet, design details and features are hard to discern given the small scale of the models, their overlapping placement, and the lighting. Shadows obscure the coat in the foreground and only the head of the other model in the foreground appears. Only one model looks boldly into the camera, while the other models look away and appear hesitant. The model with only her head visible is shrouded in shadows but enraptured, eyes closed, head turned upward.

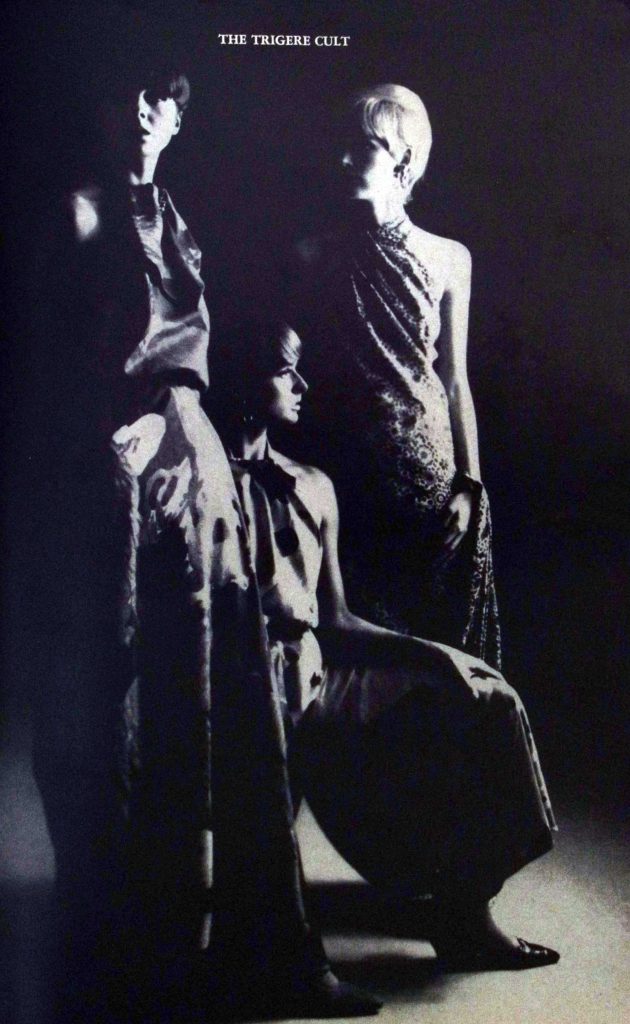

The second advertisement reduces the number of models to three but utilizes similar techniques (see Figure 2). The black and white photograph combined with the dark studio setting make it difficult to discern the intricacies of the designs. They all appear to be halter neck styles featuring skilled draping and one appears to be a jumpsuit, a design for which Trigère was well known, but colors, patterns, and embellishments are not visible. Further, the models do not look directly at the camera—two stare off into the distance with stoic expressions, while the third looks toward the front with fear and trepidation.

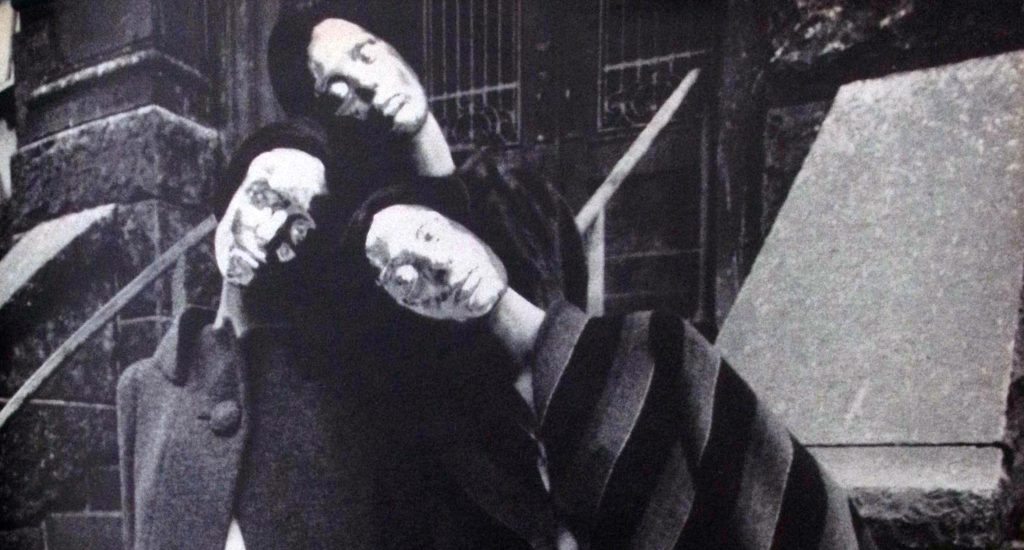

The third advertisement also features three models standing close together in a pyramid shape (see Figure 3). Unlike the others, this one is photographed outside in front of the steps into a stone building. Further, in this instance, rather than averted gazes, the models’ faces are covered with metallic masks that look blankly at the camera. The two models in the foreground wear elegant long coats that resemble robes. The coats flow seamlessly, uninterrupted by distracting pockets, darts, or embellishments. A collar and button are all that adorn one coat, while the other sports perfectly aligned chevron stripes and voluminous sleeves. The models wear long, unadorned, light-colored gowns under the coats. Interestingly, the third model’s look is not visible.

Arguably the advertisements fail to effectively highlight the garments. They are obscured by small size, poor lighting, and overlapping model placement—an odd choice for a medium intended to sell garments. Further, details about the garments, the designer, and where to purchase them are also missing. Yet the lack of informative text combined with striking poses draws attention to the provocative tagline: “The Trigère Cult.” It stands out from other fashion ads of the time given that religion and its symbols frequently appeared in fashion magazine articles and advertisements, but “cults” did not (Neal 2019).

These Trigère ads embraced an increasingly popular topic—“cults”—that fascinated Americans. Rather than focusing on one meaning, though, the Trigère ads combined both the religiously inflected “cult” stereotype with the trendy “cult following” concept. This highlights the contested and negotiated character of the term, as well as the diverse ways it was being utilized.

The ads visualized elements of the stereotype to persuade consumers to join. Their dark settings and shadowy lighting create a sense of mystery that plays into the fears and dangers associated with the “cult” stereotype. In addition, unlike most fashion photo shoots and advertisements that feature a single model, these ads utilize multiple models, which evokes the stereotypical idea of large groups of cult devotees. The models’ facial expressions, which range from stoic to fearful to masked, highlight concerns about “cult” recruitment tactics and their alleged brainwashing of those youthful devotees. Further, the inability to distinguish garment details plays into suspicions about the theological and sartorial homogeneity believed to be promoted by New Religious Movements (NRMs).

At the same time, “The Trigère Cult” also invites viewers to become “cult followers”—part of an elite, fashionable group of women. The ads seemingly hold out the promise of a community of women who share the benefits of style. However, unlike NRMs, the Trigère cult does not require extensive time commitments, new theological beliefs, or an austere moral code. One only need to make a choice and purchase a Trigère garment to join. By purchasing a garment, women were offered the status of membership—class, beauty, and belonging.

The ads made visible elements of the “cult” stereotype and utilized them to encourage consumers to become “cult followers” of Trigère. Given the public’s disdain for so-called cults and the overwhelming negativity of the stereotype, it was a bold and provocative choice. The ads exploited recognizable elements of the cult stereotype to create intrigue, while simultaneously challenging it by utilizing the “cult following” concept. By merging these two conceptions of the term, the ads highlight the contested and constructed character of the term and reframed cult membership as fashionable and desirable. In making “cult” aesthetics and allegiance aspirational, the campaign questioned the very boundaries between religious deviance and cultural sophistication that the stereotype sought to police.

Creator:

Who, though, would be daring enough to embark on such a campaign? While we lack direct evidence related to the origins of these ads, they demonstrate a certain audacity, as well as cultural awareness. In this way, the ads align with Pauline Trigére’s broader attitude and work. Personally, Trigère showed a remarkable boldness and resilience. In the late 1930s, the Jewish Trigère and her family fled France as the Nazis gained power. She started over in New York and began her eponymous house in 1942 after her husband left her and her children.

She also was not afraid of conflict, personally or professionally. For example, in 1961, she was one of the first designers to feature a Black model, Beverly Valdes, in a runway show, despite the potential (and real) fallout (Comita 2018; Seelig 2013). And in 1988, John Fairchild, founder of Women’s Wear Daily, “banned” her work from the journal “after some perceived slight.” In response, Trigère chastised him in The New York Times’ fashion magazine—in a full page “admonishment” (Comita 2018).

In addition, while she was involved in the American Jewish community, as evidenced by her co-chairing the Annual Fashion Ball sponsored by the American Jewish Committee in 1966 (Nudell 2024), she also explored different cultures, practices, and spiritualities. For example, one newspaper stated, “Pauline Trigère, Antonio Castillo and Simonetta are all big boosters of yoga. All have studied for years with noted Indian swamis in Paris and New York” (Lambert 1965).

Trigère’s boldness and refusal to shy away from potential controversy paved the way for “The Trigère Cult” ad campaign. And it did not appear to hurt her business or her legacy. Her long client list included Elizabeth Taylor, Grace Kelly, Lena Horne, and Meryl Streep (Finkle 2021). She won three Coty Awards, one of the most prestigious fashion awards for American designers at the time and was inducted into the Coty Hall of Fame in 1959. In 1993, the Council of Fashion Designers of America recognized her work with a lifetime achievement award (Seeling 2013). Designer Franklin Benjamin Elman described her as “an architect of clothing,” because “the construction is so detailed and complex” (Comita 2018, Amnéus 2010). Arguably, this ad campaign shows an equally detailed and complicated picture of “cults” and their representation in the 1960s. By exploiting the cult stereotype’s mysterious associations while also reframing membership as elite and desirable, this campaign reveals how the “cult” concept remained a contested and flexible category in the 1960s—one whose imagery could be appropriated, inverted, and commercialized even as Americans sought to consolidate its meaning.

Lynn S. Neal, Professor of Religious Studies, Wake Forest University

4 November 2025

Tags: NRMs, cult stereotype, cult following, Pauline Trigère, fashion advertising, fashion journalism

References:

“Era of Coy Flirtation Returns with New Fashions.” 1965. The Herald News (Passaic, NJ), July 8, 14.

Bromley, David G., and Douglas E. Cowan. 2023. Cults and New Religions: A Brief History. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Carter, Joyce. 1965. “Near-Nudity Highlights Fashion Show.” The Globe and Mail (Toronto), July 10, 11.

Comita, Jenny. 2018. “How Trigère, a Historic Fashion Label Ahead of Its Time, Was Suddenly Reborn.” W Magazine, August 20. Accessed October 29, 2025. Available at:

https://www.wmagazine.com/story/trigere-designer-franklin-benjamin-elman.

Dillon, Michele, and James T. Richardson. 1994. “The ‘Cult’ Concept: A Politics of Representation Analysis.” Syzygy: Journal of Alternative Religion and Culture 3 (3–4): 185–97.

Emery, Joy Spanabel. 2014. “New Challenges: 1960s–1980s.” In A History of the Paper Pattern Industry: The Home Dressmaking Fashion Revolution, 178–94. London: Bloomsbury Academic. Accessed October 1, 2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/9781474223775/JEHISPPI0013.

Finkle, Dana. 2021. “Pauline Trigère: Profiles in Sewing History.” Threads Magazine, September 21. Accessed October 29, 2025. Available at: https://www.threadsmagazine.com/2021/09/21/pauline-trigere-profiles-in-sewing-history.

Kelly, Venita. 1965. “Battle of Belts Rages On.” The Cincinnati Post, May 11, 17.

Lambert, Eleanor. 1965. “Keep Slim and Limber.” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, May 10, B4.

Neal, Lynn S. 2019. Religion in Vogue: Christianity and Fashion in America. New York: New York University Press.

Ridings, Dorothy. 1965. “Mad, Mad Fashions Bow to Elegance.” The Charlotte Observer, July 11, E1.

Seelig, Surella Evanor. 2013. “Pauline Trigère Papers.” Brandeis University Special Collections, August 1. Accessed October 29, 2025. Available at: https://www.brandeis.edu/library/archives/essays/special-collections/trigere.html.

Walker, Alyce B. 1965. “Fashionalities in Bagdad-on-the-Hudson.” The Birmingham News, July 4, D1.

Further Research: Pauline Trigère Archival Collections

Researchers interested in viewing Pauline Trigère’s garments, sketches, and personal papers may wish to consult the following collections:

- Mount Mary University Fashion Archive — Digital fashion archive featuring Trigère designs

https://digitalcollections.mtmary.edu/exhibits/show/mountmaryuniversityfashionarch/digitalfashionarchive/designers/paulinetrigere - Kent State University Museum — Pauline Trigère Collection

https://oaks.kent.edu/trigere - Brandeis University Special Collections — Pauline Trigère Papers

https://findingaids.brandeis.edu/repositories/2/resources/83