1984 Madonna’s MTV Awards Look

Religion: Christianity

Time Period: 1980s

Type Of Garment: Dress

Tags: Catholicism, Ceremonial, Culture Wars, Madonna, United States, Wedding Dress

The Object:

The “Queen of Pop,” Madonna, has influenced mainstream culture since the 1980s. She is known for pushing boundaries around gender, sexuality, music, and religion. In doing so, she has challenged systems and advocated for women’s rights, as well as LGBTQ+ rights. One of the first and most notable instances of this advocacy occurred at the inaugural 1984 MTV Video Music Awards. During this show, Madonna’s creative and provocative performance of “Like a Virgin” catapulted her into superstardom and controversy. It was, according to one observer, “the award-show equivalent of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address — the ideal against which all successors would be measured” (Gabriel 2023). And a representative from MTV noted, “that three minutes in 1984 was the point when Madonna became a superstar” (Gabriel 2023). Dressed in a skin-forward wedding dress with bold accessories, Madonna exuded sex appeal as she both captivated and polarized viewers. Her iconic outfit and its religious imagery confronted traditional ideas about Christianity, especially Catholicism, women, and sexuality in the 1980s.

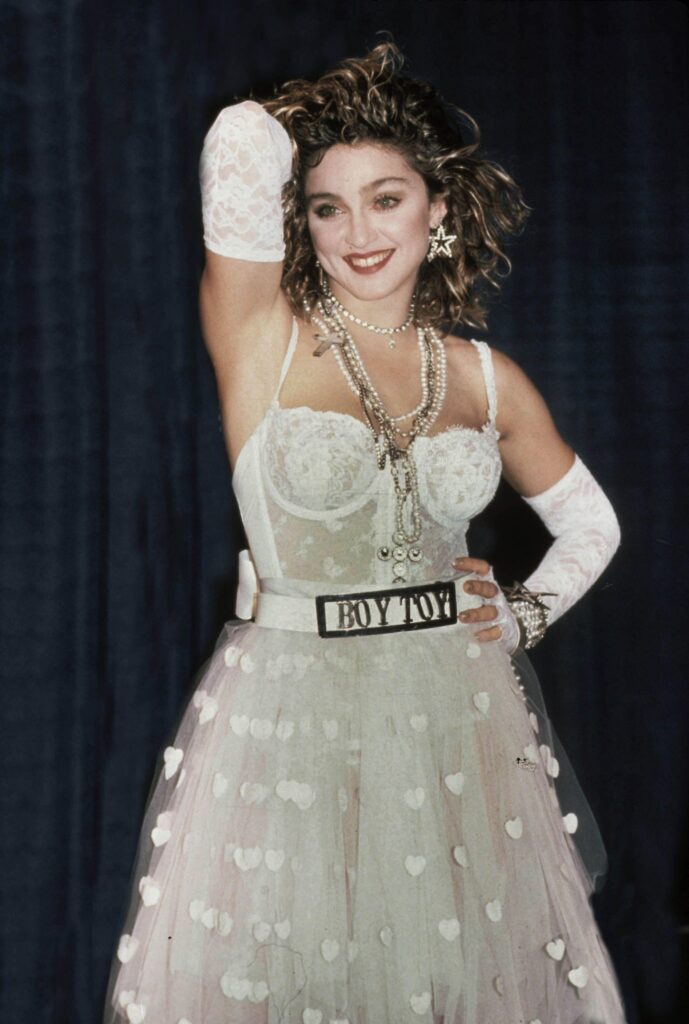

At the event, Madonna wore a white lace wedding dress. The corset-style top featured numerous sheer and see-through sections. She wore white lace, fingerless gloves that extended above her elbows topped with chunky bracelets and bangles. The pearls in her bracelets matched those found in her long, beaded necklaces—one being a rosary and another a cross. Her silver belt read “BOY TOY” and she wore white heels with a white bows on top (See Figure 1).

Madonna’s look gained attention and sparked controversy, in part, because of how it upended traditional notions of the wedding dress. Historically, in the American context, wedding dresses are white and associated with purity and modesty. Further, “in Christian communities the religious associations of the white wedding dress remain important” (Ehrman 2011, 17). For example, a wedding dress designed in 1940 highlights these traditional attributes through its white color, long sleeves, floor length skirts, and a modest neckline all made out of a not sheer fabric (see Figure 2). This trend continued in the 1980s. At arguably the wedding of the decade (if not the century), Princess Diana’s wedding dress took center stage and highlighted modesty with its puffy sleeves and voluminous skirt (see Figure 3).

Madonna’s wearing of a short, sheer, and sleeveless wedding dress during her performance of “Like a Virgin” challenged these traditional and religious connotations. The corset top, spaghetti straps, and sheer fabric of the dress highlighted its resemblance to lingerie. Further, Madonna’s dance moves and the song lyrics amplified the sexuality of her look and subverted notions of purity associated with wedding dresses. As one reporter noted, “dressed in a white wedding dress complicated by a series of straps and buckles that suggested a sadomasochistic jumpsuit, Madonna writhed on the floor while cooing her song, moaning and thrusting various parts of her body at the audience” (Tucker 1984). Her performance represented a vision of femininity that reveled in its control and expression of sexuality, which challenged the dominant norms in the 1980s. It made a powerful and controversial statement.

Madonna’s chosen accessories further highlighted the transgressive stance embodied in this look. Along with numerous strands of pearls, Madonna wore a cross pendant and a rosary as a necklace. While this trend has become somewhat commonplace in the 21st century, Madonna was one of if not the first celebrity to wear a rosary in this way. Traditionally, the rosary is a tool for prayer–the beads serve as an aid to “a ritually repeated sequence of prayers accompanied by meditations on episodes in the lives of Christ and Mary” (Mitchell 2009). It is a devotional instrument, not a decorative item. Thus, wearing it as jewelry layered over her sexualized look while performing “Like a Virgin” proclaimed Madonna’s power to redefine the symbol on her own terms and to challenge Catholic stances on women, religion, and sexuality.

In addition, Madonna’s “BOY TOY” belt represented sexual empowerment and challenged gender stereotypes. The belt highlighted her sexual freedom and women’s choices. According to one report, when describing the “Like a Virgin” album cover, in which Madonna wore a similar look, she explained, “The photo was a statement of independence, if you wanna be a virgin, you are welcome. But if you wanna be a whore, it’s your right…to do so” (Princess Gabbara 2023). Madonna’s proclamation of women’s sexual freedom challenged the increasingly conservative evangelical and Catholic religious climate of the 1980s.

The Context:

During the 1980s, “conservatism rose in social, economic, and political life,” (History.com Editors, 2023). This occurred in the religious realm as the Christian Right, led by figures such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, gained political power and forged powerful conservative alliances across religious traditions. Evangelical Protestants, conservative Catholics, and others joined together to shape American culture by protesting abortion, censoring music, and voting red. This deepened what sociologist James Davison Hunter called, “the culture wars,” a battle over “our most fundamental and cherished assumptions about how to order our lives–our own lives and our lives together in this society” (1991, 42; see also McNamara 1985).

Some forms of popular culture aligned with these values. For example, television highlighted the centrality of nuclear families in popular shows, such as “The Cosby Show” (1984-1992) and “Roseanne” (1988-1997). And Christian bookstores boomed–selling Christian books, music, and apparel. However, in the sphere of pop and rock music, some artists, Madonna, Prince, Michael Jackson, and others, along with the increasing popularity of rap and heavy metal challenged this cultural shift. MTV presented a medium for artists working “against the grain” (History.com Editors, 2023). Amidst this battle, Madonna entered the fray with her provocative lyrics, sexualized dance, and sheer wedding dress, while laying claim to the cross and rosary. As the culture wars fought over “the symbols of legitimacy,” Madonna’s look and performance created space for religious doubt, challenge, and critique (Davison Hunter 1991, 147).

The Wearer:

Madonna embraced the role of provocateur and soldier in the culture wars. She explained, “I know the moral majority is up in arms against me but I consider that an achievement. I know I’m offending certain groups but I think that the people who understand what I’m doing are not offended because it’s pro-life, it’s pro-equality and it’s pro-humanity” (Neal 2019, 113-114). Born in 1958 in Michigan, the Italian American Madonna Louise Ciccone grew up in a Catholic family, as evidenced by her given name. While deeply shaped by her family’s devotion and attending Catholic elementary school, Madonna the adult and artist struggled with the tradition’s rigidity and conservatism. In one interview she explained, “the theme of Catholicism runs rampant through my album. It’s me struggling with the mystery and magic that surrounds it. My own Catholicism is in constant upheaval.” She added, “I renounced the traditional meaning of Catholicism in terms of how I would live my life, but I never stopped feeling the guilt and shame that are ingrained in you if you are brought up Catholic” (Neal 2019, 113). These struggles shaped her music and spoke to a younger generation, who sought to emulate her style and sexual freedom, if not her spiritual quest.

After her MTV Video Music Awards performance, industry executives and her own manager feared Madonna’s had gone too far and jeopardized her career. She was criticized by the press and other artists. However, as she left the venue, teenagers and young adults were waiting in the street for Madonna, cheering her name (Gabriel 2023). She had tapped into something powerful–in culture, religion, and fashion. A year later, in 1985, “the Associated Merchandising Corporation…recommended that its member department stores open FTV, or fashion television, boutiques. Macy’s has featured shops named Madonnaland (Neal 2019, 89). People of all backgrounds were influenced by her style and boundary-pushing stances, which continued after this performance. A few years later, she dedicated “Papa Don’t Preach” to Pope John Paul II after he criticized her work and urged fans to avoid her concerts. Tensions with the Pope occurred again in 1989, when the Pope censured her “Like a Prayer” music video.

Madonna’s 1984 look provided this culture war soldier with a powerful uniform in which to battle the conservative religious and cultural forces of the decade. She faced immense criticism for flouting the cultural and Christian conventions that constrained women and sexuality. Others, though, loved her, her look, and her transgressive attitudes. Her popularity soared. She created new fashion trends and alternative spiritual places–for questioning and critique. She challenged pervasive conservative religious ideals in the 1980s, fueled discussions of female autonomy in religious spaces, and continued the conversation in contemporary culture. As one young woman described it. “Madonna was an icon of teenage female rebellion, providing alternatives to the traditional, established definitions of womanhood and femininity.” She continued, “Her name, Madonna, meaning “virgin,” represents the ultimate image of the Catholic, devoted, submissive, and nurturing woman, an image that we knew too well from our upbringing and culture. Yet Madonna’s demeanor gave other meanings to the image of the Madonna brokered to us by the Catholic Church. Madonna was a contradiction, and that helped us come to terms with our own contradictory reality” (Lugo-Lugo 2001).

Zoe Brown, Politics and International Affairs Major, Religious Studies and Statistics Minors (WFU ‘26).

10 October 2024

Tags: Catholicism, Ceremonial, Culture Wars, Madonna, United States, Wedding Dress

References:

Davison-Hunter, James. 1991. Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. New York: Basic Books.

History.com Editors. 2018. “1980s: Fashion, Movies & Politics.” History.com, 23 August. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/1980s/1980s.

Ehrman, Edwina. 2011. The Wedding Dress: 300 Years of Bridal Fashions. London: V&A Publishing.

Gabriel, Mary. 2023. “Inside Madonna’s Legendary Performance at the First VMAs.” Rolling Stone, 27 September. Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/madonna-vmas-biography-excerpt-1234829918/.

Lugo-Lugo, Carmen R. 2001. “The Madonna Experience: A U.S. Icon Awakens a Puerto Rican Adolescent’s Feminist Consciousness.” Frontiers 22 (2): 118. https://doi.org/10.2307/3347058.

McNamara, P. H. 1985. “American Catholicism in the Mid-Eighties: Pluralism and Conflict in a Changing Church.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 480 (1): 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716285480001006.

Mitchell, Nathan D. 2009. The Mystery of the Rosary: Marian Devotion and the Reinvention of Catholicism. New York: New York University Press.

Neal, Lynn S. 2019. Religion in Vogue: Christianity and Fashion in America. New York: New York University Press.

Princess Gabbara. 2023. “Songbook: How Madonna Became The Queen of Pop & Reinvention, From Her ‘Boy Toy’ Era to The Celebration Tour.” Grammy.com, 27 July. Available at: https://www.grammy.com/news/madonna-albums-songs-celebration-tour-queen-of-pop-legacy-40th-anniversary.

Tucker, Ken. 1984. “Madonna May Appall Critics, But Her Music’s Not All Bad.” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 2, F3.