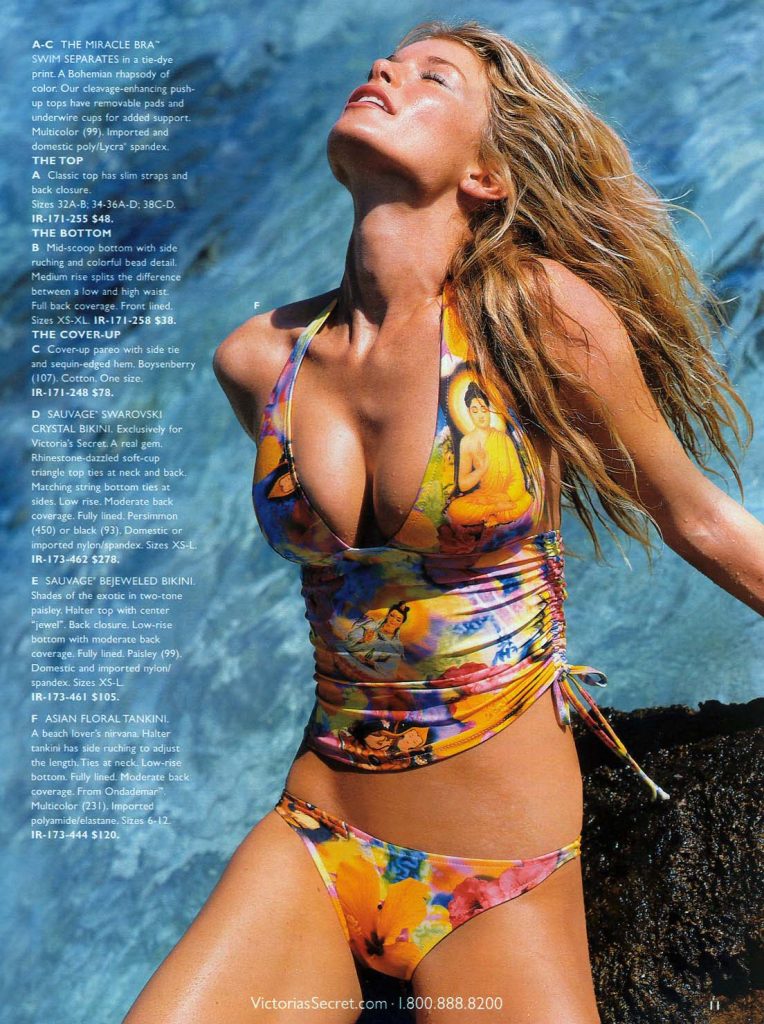

2004 “Asian Floral Tankini” by Victoria’s Secret

Religion: Buddhism

Time Period: 2000s

Type Of Garment: Bathing Suit

Tags: Advertising, Bathing Suit, Blasphemy, Buddha, Buddhism, Commodification, Everyday, Globalization, Ondade Mar, Sexuality, United States, Victoria’s Secret

The Object:

The “Asian Floral Tankini” was introduced by Victoria’s Secret in its 2004 summer catalog, part of a broader trend in early-2000s Western fashion that appropriated “exotic” motifs from East and South Asia (see Figure 1). At first glance, the bikini appeared as a bright, decorative summer garment, its red, purple, and orange floral patterns evoking a generalized “Oriental” aesthetic common in mainstream fashion advertising. Closer examination, however, revealed a far more specific visual vocabulary: the design included carefully rendered Buddhist iconography drawn from Tibetan thangkas. Unlike many fashion appropriations that relied on vague or stylized references, the figures on this garment were recognizably canonical.

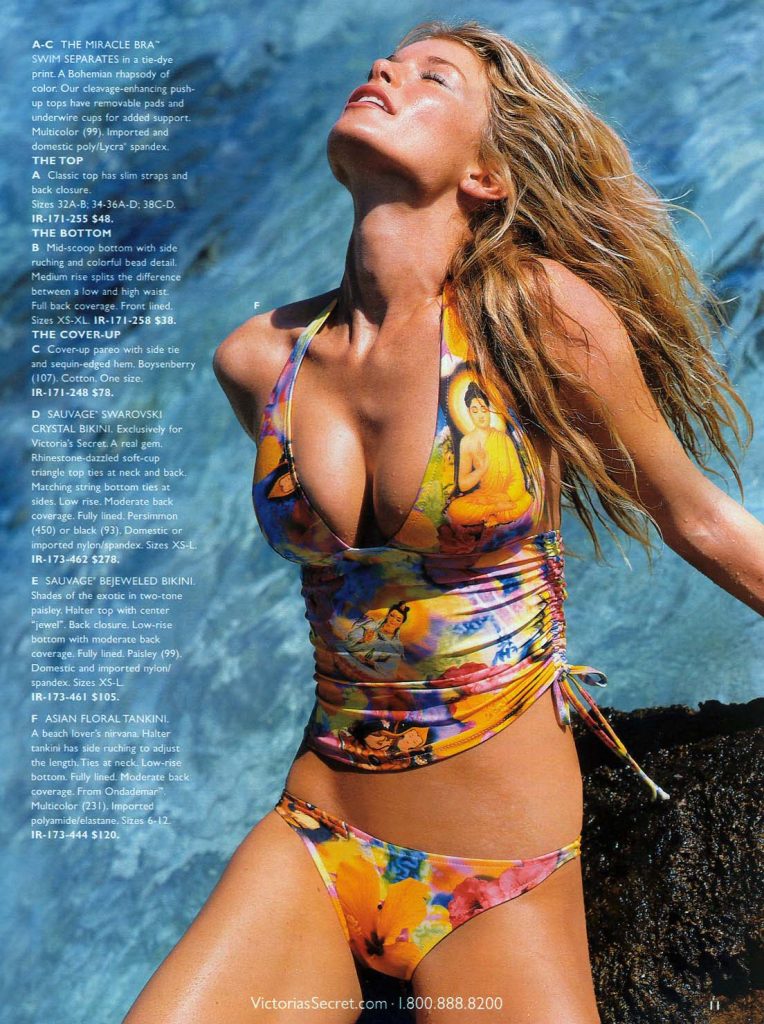

(c) Victoria’s Secret.

(c) Victoria’s Secret.

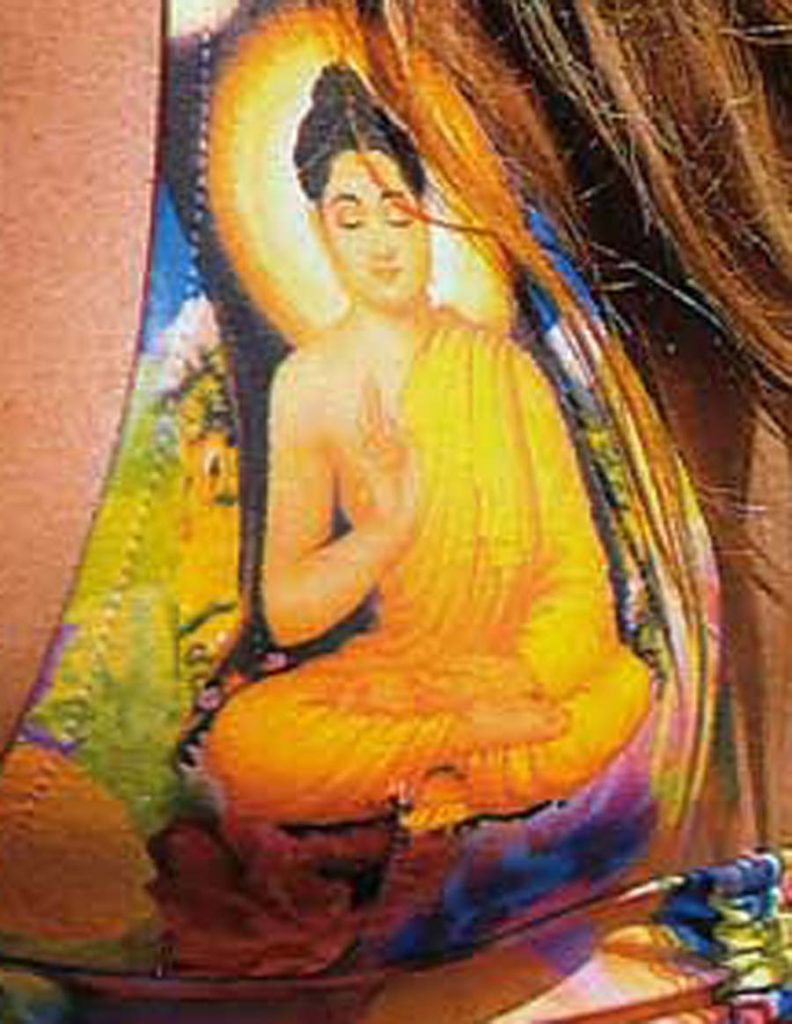

The central figure on the bikini top depicts the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni (c. 563–483 BCE), seated in meditation. His hands form a combination of the teaching and meditation mudras, indicating both his identity and his enlightened state (See Figure 2). Across the torso, the blue-robed Bhaisajyaguru, or Medicine Buddha, appears with his right hand raised in the gift-giving mudra and his left hand holding a jar of healing nectar, echoing the iconography associated with his lapis lazuli paradise (See Figure 3). Above the bikini’s hemline, cropped at the model’s midriff, is Tsongkhapa (Je Rinpoche, 1357–1419), founder of the Geluk or “Yellow Hat” school of Tibetan Buddhism, depicted with his distinctive yellow hat and monastic robes. In Tibetan tradition, he is revered as a “second Buddha,” an emanation of the bodhisattva Manjushri (see Figure 4).

(c) Victoria’s Secret.

(c) Victoria’s Secret.

The placement of these sacred figures on a seasonal swimsuit created a dissonant effect. In their traditional context, such images are ritually consecrated, enshrined in temples, and treated with reverence. On a bikini, they became commodified and sexualized, part of a fashion cycle in which garments are designed to be visible, consumable, and disposable. As Bernard Faure observes, the verisimilitude of Asian icons “because of their mimetic quality, are able to arouse people” (Faure 1998: 780). In this case, the accuracy of the imagery only intensified the tension between sacred meaning and commercial use.

The bikini thus exemplifies the complex intersection of fashion, globalization, and religious imagery in early-21st-century consumer culture. While visually striking, the garment raised questions about cultural and spiritual appropriation, demonstrating how objects intended for sacred veneration can be transformed into consumable commodities for mass audiences.

The Creator:

The “Asian Floral Tankini” was designed under contract with OndadeMar, a Colombian swimwear company known for drawing inspiration from global folk art. While neither OndadeMar nor Victoria’s Secret had any religious connection to Buddhism, the swimsuit’s print displayed unusual iconographic precision. Unlike the vague lotus blossoms or generic “Zen” motifs common in fashion, this design included identifiable figures: the historical Buddha (Shakyamuni), the Medicine Buddha, and the Tibetan master Tsongkhapa.

This realism was both striking and problematic. It suggested that the designers had worked directly from Buddhist paintings or prints, yet stripped them of ritual and religious context. What in a temple might serve as an object of veneration became, on a bikini, a provocative “exotic” flourish.

And yet, if we suspend judgment about corporate intention and the profit motive, a paradox emerges. In mass-producing accurate images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, OndadeMar and Victoria’s Secret inadvertently participated in a very old Buddhist logic: the idea that sacred images themselves radiate salvific power. Buddhist traditions have long held that the reproduction and circulation of icons can generate merit and spread blessings, regardless of the maker’s or viewer’s awareness. From this perspective, the “Buddha bikini” not only commodified Buddhist imagery, but also—however unintentionally—helped propagate it.

The tension here lay not only between tradition and innovation, but also between sacred efficacy and commercial exploitation. By using highly realistic Buddhist imagery, OndadeMar and Victoria’s Secret blurred the line between authenticity and appropriation, producing a product that was, paradoxically, both more accurate and more offensive than other examples of religious fashion.

The Reception:

Little is known about who purchased or wore the Buddha bikini, as it was pulled from stores almost immediately after its release. The controversy surrounding the garment, however, was widely documented. Buddhist organizations in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the United States lodged formal complaints. Monks in Colombo condemned it as sacrilegious, while Thai consumer groups called for a boycott of Victoria’s Secret stores. Asian American Buddhists expressed dismay online, noting that although Abercrombie & Fitch had previously produced a Buddha-head T-shirt, the bikini represented a new level of commercialization: not merely trivializing Buddhist figures, but explicitly sexualizing them.

Victoria’s Secret responded by insisting that the print was “merely decorative” and quickly discontinued the item. By the time it was withdrawn, however, media coverage had circulated globally, ensuring that the garment’s cultural impact far outstripped its physical presence in stores. For many observers, the incident highlighted the extent to which Western corporations either misunderstood or disregarded the sacred status of Buddhist imagery.

Some critiques, however, may also have reflected conservative—and even misogynistic—views on gender and the body within Buddhist contexts. Across many traditions, women’s bodies have been framed ambivalently—seen simultaneously as sites of fertility and compassion, yet also as impure or distracting. From this perspective, the offense was compounded by placing sacred icons on a mass-produced swimsuit worn by women. The controversy thus intersected both with questions of cultural appropriation and with ongoing patriarchal assumptions embedded in global Buddhist discourse.

Because the swimsuit was sold only briefly, little is known about wearers’ own experiences or interpretations. In this sense, the garment’s significance is defined less by who wore it than by the debates about its propriety, which circulated widely in media and online forums, shaping public understanding of the tensions between fashion, spirituality, and cultural respect.

The Context:

The Buddha bikini emerged in the early 2000s, a period when global fashion brands increasingly incorporated religious and “ethnic” motifs for their exotic appeal. Christian icons on jewelry, Hindu deities on T-shirts, and “yoga chic” apparel all circulated widely, creating a consumer landscape in which sacred symbols could be repurposed as aesthetic decoration. In this context, the Buddha bikini was not an isolated anomaly but rather an extreme manifestation of a broader trend: the commodification of religious imagery as fashion statements.

Several factors contributed to the prominence and controversy of this garment. First, textual Buddhist traditions often portray women’s bodies as potential sites of distraction or impurity, yet visual traditions include powerful female figures such as yakshis, dakinis, Tara, and Guan Yin. The bikini therefore intersected with longstanding anxieties around gender, desire, and the body: the aestheticization of Buddhist imagery was predictable, but situating these images on a sexualized garment rendered them particularly provocative.

Second, the global backlash reflected changing Buddhist demographics and activism. By 2004, immigrant Buddhist communities in North America, along with second- and third-generation Asian American Buddhists, were increasingly vocal about cultural appropriation. Online forums and social media amplified their concerns, making it difficult for corporations to dismiss criticism quietly.

Viewed retrospectively, the Buddha bikini anticipates debates that have only intensified in the decades since its release: over the use of sacred symbols in fast fashion, festival culture, and wellness industries; over who is authorized to deploy religious imagery; and over the limits of commodification in a global religious marketplace. While its circulation was brief, the garment highlights the intersection of fashion, spirituality, and consumer ethics in a moment of heightened global cultural exchange.

James Mark Shields, Professor of Comparative Humanities and Asian Thought at Bucknell University

6 September 2025.

Tags: bathing suit, bikini, Buddha, orientalism, globalization, advertising, commodification, sexuality, blasphemy, United States, Victoria’s Secret, Ondade Mar

References

Faure, Bernard. 1998. The Red Thread: Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shields, James Mark. 2010. “Sexuality, Exoticism, and Iconoclasm in the Media Age: The Strange Case of the Buddha Bikini.” In God in the Details: American Religion in Popular Culture, revised 2nd edition, edited by Eric M. Mazur and Kate McCarthy, 80–101. London: Routledge.