1997 The Jesus Piece

Religion: Christianity

Time Period: 1990s

Type Of Garment: Jewelry

Tags: Black Style, Chain, Christianity, Ghetto Fabulous, Hip Hop, Jesus, Rap

Object

Over a hip-hop beat that samples the 1979 disco instrumental “Rise” by Herb Alpert, The Notorious B.I.G. (a.k.a. Biggie Smalls, born Christopher Wallace) raps, “Cubans with the Jesus piece, with my peeps (thank you, God)” in his 1997 hit single “Hypnotize.” In the music video for this single, Sean Combs, then known as the founder of Bad Boy Records, reaches for and holds up the gold chain necklace hanging from Wallace’s neck for the camera. Throughout the rest of the video, the chain, a Jesus piece, is on full display (see Figure 1).

The official music video for “Hypnotize” by The Notorious B.I.G.

The Jesus piece is a pendant worn at the end of a chain necklace, depicting the face of Christ crowned with thorns. While the pendant can be crafted from a variety of metals, it is most often rendered in gold and set with diamonds or other precious stones (see Figure 2). Cheaper versions made from non-metals such as wood or plastic are also available. Within the pendant itself, precious gemstones can be added, typically to the eyes or crown of thorns. In recent decades, with the increased popularity of “bling,” the entire pendant may be encrusted with diamonds or gemstones.

The religious significance of this object lies, quite obviously, in the depiction of Christ’s likeness. Author Joe Nickell notes that given the lack of a complete description of Christ’s appearance, there have been several varying attempts at portraying the likeness of Christ throughout visual culture (Nickell 2007). Early images that were believed to bear the true likeness of Christ, such as the Image of Edessa and Veronica’s Veil, set a precedent for imagining and reproducing Christ’s face. Images of Christ’s face merged divinity, materiality, and image-making, serving as miraculous portraits that reflect the enduring human desire to visualize the divine and authenticate faith through an image (Nickell 2007).

Regarding the Jesus piece, the face of Christ references this desire, alongside culturally and situationally specific symbols. The pendant participates in this long visual tradition but reframes it through hip hop’s theological and material logics, where Christ’s face becomes a site for expressing survival, status, and identification with a figure understood to share the burdens of marginalization. In doing so, the Jesus piece adapts the sacred portrait into an object that mediates both faith and lived experience.

Creator

The disputed originator of the Jesus piece style is rapper Ghostface Killah, a member of the Wu-Tang Clan, who wore the pendant in the music video for the 1995 song “Incarcerated Scarfaces.” However, The Notorious B.I.G. is credited with popularizing the style. Neither Ghostface Killah nor The Notorious B.I.G. practiced Christianity, the religion most associated with the figure of Jesus, at the time they adopted the style. Ghostface Killah is a convert to Islam, and The Notorious B.I.G. was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness. Both traditions acknowledge Jesus, though their interpretations differ from mainstream Christian doctrine.

Over time, the style was taken up by rappers such as Jay Z, Kanye West, The Game, and Rick Ross. Of these artists, The Game and Rick Ross identify as Christians, and Kanye West identified as Christian in the past, though his current religious identity is unclear. The history of the pendant shows that neither its originators nor its early popularizers relied on a shared religious commitment. This suggests that the adoption of Jesus’s likeness in hip hop draws on cultural, visual, and symbolic associations that exceed formal religious affiliation.

Context

The adoption of Christ as a symbol extends to the Black community at large. Historically, enslaved Africans connected to Jesus through shared experiences of suffering and oppression, seeing him as a companion and liberator. However, for enslaved Black people, Jesus was often imagined as white, something that would be challenged in the early twentieth century. In the 1920s–1930s, leading Black cultural figures like Marcus Garvey and Langston Hughes advanced an explicitly Black Jesus to affirm Black dignity, boost self-esteem, and resist white supremacy (Hart 1967; Culp 1987).

This reinterpretation has continued into the present, not only in religious life but within hip hop. Artists either embrace a Black Jesus as an empathetic ally or critique Christianity’s limits by casting him as a figure who exposes the failures of the faith to secure Black freedom (Utley 2012; Tinajero 2013). Rappers identify with Jesus because his life mirrors their own conditions: he grew up poor, faced state oppression, challenged authority, associated with the marginalized, and was ultimately betrayed and executed (Utley 2012; Tinajero 2013). Rappers see their own trajectories in this narrative, framing Jesus as a figure who, like them, endures surveillance, hardship, and public judgment while speaking truth to power. This creates a narrative structure in which Jesus becomes a model for survival under structural constraint. The Jesus piece amplifies this identification by materializing Christ’s face at the center of hip-hop’s bodily display, allowing wearers to signal proximity to a suffering-yet-triumphant figure whose story affirms their own.

Given this context, references to Jesus exist within hip-hop in a range of ways. For example, Clipse (a rap duo composed of Pusha T and Malice) depict a Black Jesus riding with them on a drug run on their first commercial album Lord Willin’ (2002). Interestingly, Professor of Communication Studies Ebony A. Utley explains that fans did not find this image offensive because it represented Jesus as a loyal companion who understands the structural conditions shaping their choices and offers protection, possibility, and solidarity without judgment (2012: 51).

Utley further argues that Jesus functions as what she calls the “gangsta’s God,” a figure who remains present in contexts marked by poverty, violence, and surveillance (2012). This is evident in Kanye West’s 2004 song “Jesus Walks,” where West locates Jesus in the postindustrial hood and uses Christ’s presence to affirm that those navigating systemic hardship are accompanied by a divine figure who walks with them through their realities. This adoption of Jesus as a companion extends into fashion, as rappers embrace Jesus’s likeness through chain necklaces with pendants shaped into crucifixes and crosses, and, of course, the Jesus piece. The Jesus piece becomes one more site where Christ’s image is reinterpreted as a figure who shares the burdens of marginalization while signaling status, endurance, and cultural memory.

Wearer

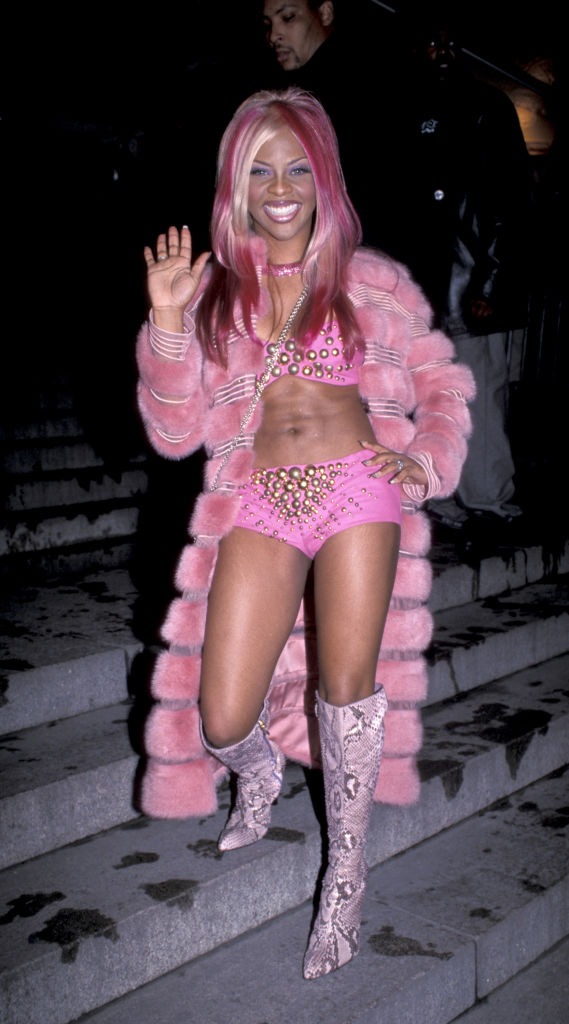

As hip hop gained mainstream visibility, the Jesus piece shifted from a subcultural emblem to a widely adopted fashion accessory. One likely reason could be the adoption of a ghettofabulous aesthetic in the 1990s (see Figure 3). Ghetto fabulousness is a subcultural style that emerged in the 1980-1990s and aesthetically combined streetwear with high-end luxury (Mukherjee 2006; Mukherjee 2009). It was originally associated with hip hop through its adoption by rappers such as Jay Z and Lil Kim.

Ghetto fabulousness, popularized by Black cultural icons in hip-hop, used bold, luxurious fashion and accessories to challenge negative stereotypes and express Black working-class empowerment amid harsh socio-economic and racial conditions. This style symbolized a reclaiming of wealth and success as a form of resistance and redefinition of the Black American dream within a racialized capitalist society (Mukherjee 2006; Mukherjee 2009). The choice of materials within the Jesus piece is central to this alignment.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Black Americans increasingly embraced Afrocentrism in personal style, and were interested in learning about their ancestral roots in Africa (Shackelford 2022). Part of this new knowledge involved the realization that pre-colonial Africans adorned themselves with gold through elaborate jewelry or by putting gold flakes in their hair (Ford 2019, chapter 8). Within hip hop, gold also served as a visible marker of musical success. Artists who achieved gold status on their records, selling over 500,000 units, reflected this achievement through large gold necklaces and rings. As the genre expanded and artists reached multiplatinum status, selling over one million units, jewelry shifted from gold to platinum and diamond-encrusted forms, materializing this new level of success (Osse and Tolliver 2006). The Jesus piece, rendered in these metals and stones, became a logical object through which rappers could express economic mobility, personal narrative, and aesthetic affiliation with ghetto fabulousness.

The religious rhetorical output of many rappers, both textual and visual, points to a Christian ethos shaped by their specific social contexts, emphasizing solidarity with Jesus as a figure of suffering, a mistrust of organized religion, and an ongoing struggle between good and evil. This ethos is expressed not only in lyrics and imagery but also in material objects like the Jesus piece, which translates Christ’s likeness into a wearable symbol of survival, status, and marginalization.

As hip hop shaped mainstream fashion through music videos, magazines, and collaborations with luxury brands, non-rap audiences adopted the Jesus piece as part of a broader engagement with hip hop’s visual codes; its blend of religious imagery, material display, and cultural symbolism made it legible to consumers seeking to emulate the look of rap stardom. The widespread circulation of the Jesus piece demonstrates how ghettofabulous aesthetics, fueled by hip hop’s cultural authority, transformed the pendant from a subcultural marker into a mainstream object of style. Together, these dynamics reveal how hip hop’s reimagining of Christ’s image functions as both social critique and cultural production, carrying theological meaning even as it enters new markets and acquires new audiences.

Lauryn Grubbs, PhD Student in Apparel Design, Cornell University

21 November 2025

Tags: Jesus, Chain, Hip Hop, Rap, Christianity, Black Style, Ghetto Fabulous

References:

Culp, Mary Beth. 1987. “Religion in the Poetry of Langston Hughes.” Phylon 48 (3): 240–45.

Ford, Tanisha C. 2019. Dressed in Dreams. St. Martin’s Press Ford.

Hart, Richard. 1967. “The Life and Resurrection of Marcus Garvey.” Race 9 (2): 217-237.

Mukherjee, Roopali. 2006. “The Ghetto Fabulous Aesthetic in Contemporary Black Culture: Class and Consumption in the Barbershop Films.” Cultural studies 20 (6): 599-629.

Mukherjee, Roopali. 2009. “’Ghetto Fabulous’ in the Imperial United States: Black Consumption and the ‘Death of Civil Rights.’” In Rethinking America: The Imperial Homeland in the 21st Century, edited by Jeff Maskovsky and Ida Susser. Routledge.

Nickell, Joe. 2007. Relics of the Christ. University Press of Kentucky.

Osse, Reggie and Gabriel Tolliver. 2006. Bling: The Hip-Hop Jewelry Book. Bloomsbury Rooks.

Shackelford, Carolinie. 2022. “The Evolution Of Hip-Hop Fashion: Origins To Now.” He Spoke Style. February 25, 2022. https://hespokestyle.com/hip-hop-fashion/.

Tinajero, Robert. 2013. “Hip hop and Religion: Gangsta Rap’s Christian Rhetoric.” The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 25 (3): 315-332.

Utley, Ebony A. 2012. Rap and Religion: Understanding the Gangsta’s God. Bloomsbury.