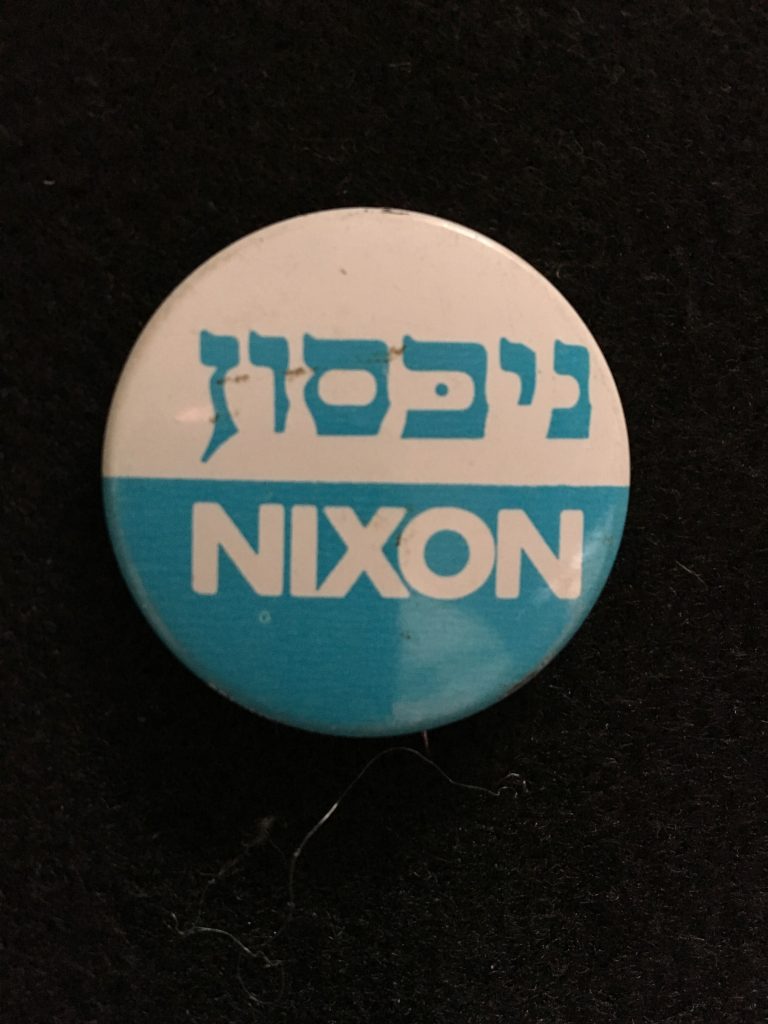

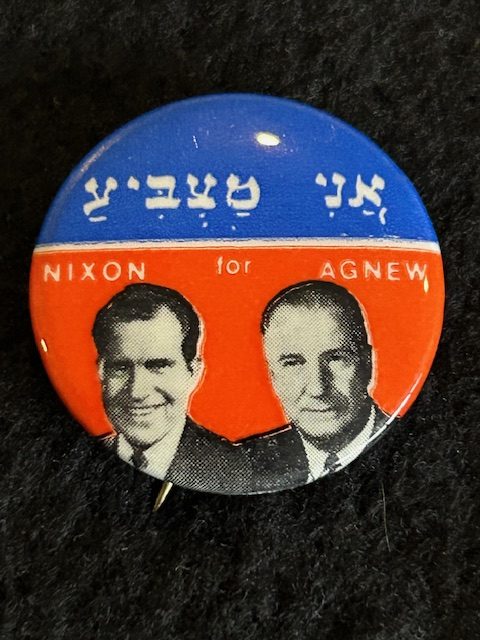

1972 Hebrew Nixon Presidential Campaign Button

Religion: Judaism

Time Period: 1970s

Type Of Garment:

Tags: , Eisenhower, Jews, Judaism, Nixon, , politics, presidential campaigns, Reagan

Object:

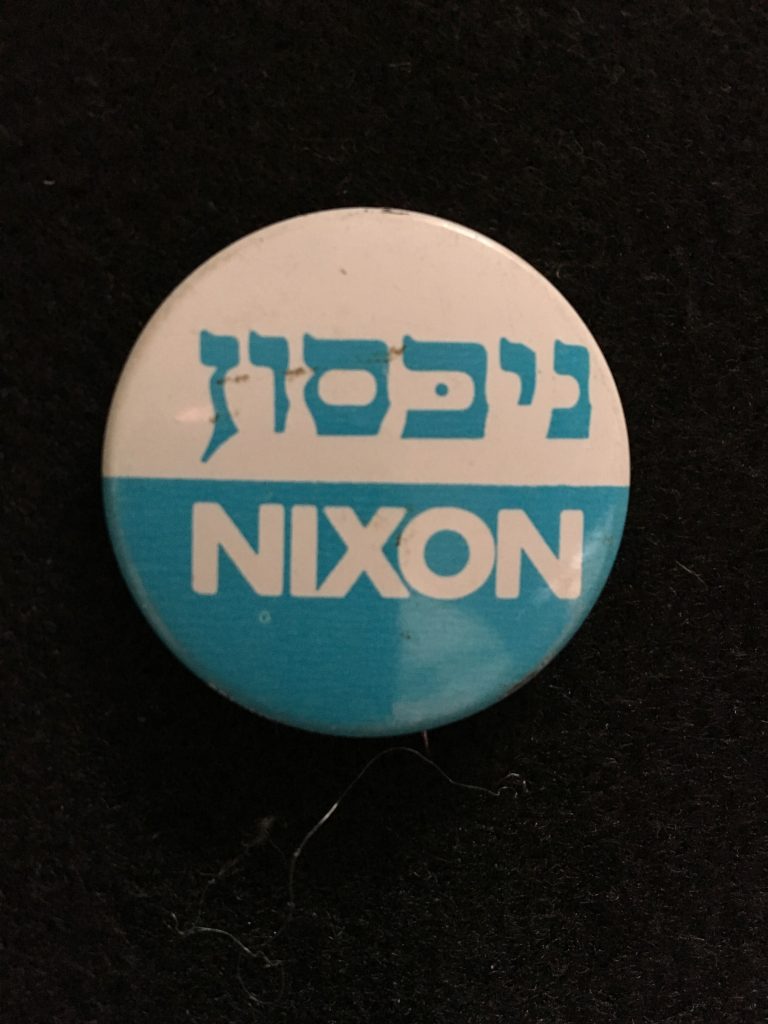

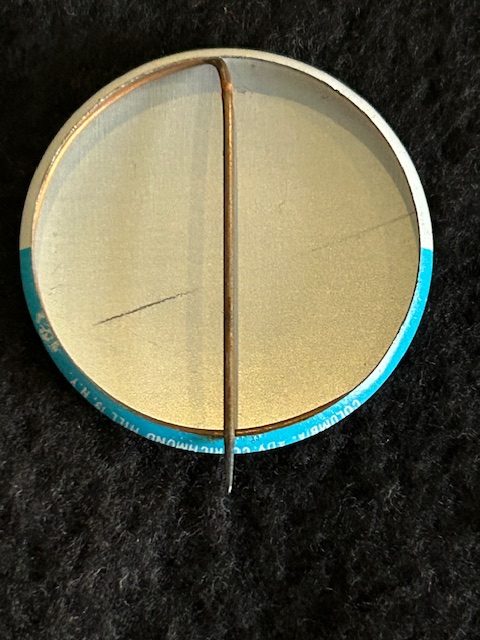

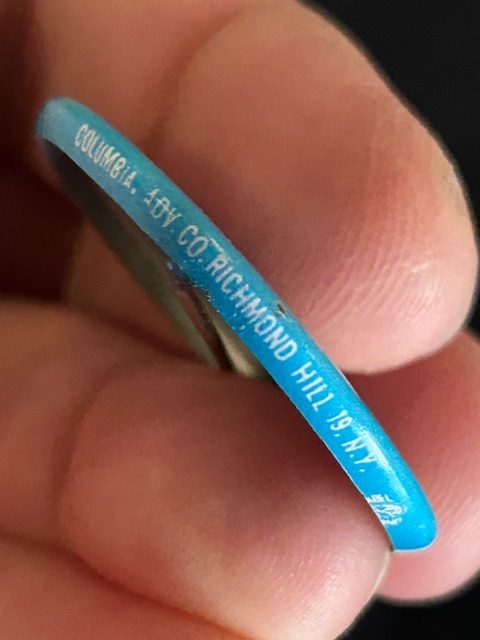

This Hebrew/English button appeared in the 1972 presidential campaign, with Nixon’s name transliterated in blue Hebrew letters on a white background above his name in English on a blue background (see Figure 1). Made of metal with a celluloid coating and pin-back, the button was manufactured by the Columbia Advertising Company in Queens, New York (see Figure 2). The company, run by Al Cohen, sold campaign paraphernalia—buttons, but also bumper stickers, bunting, posters, and event-related materials like floats and lights—to candidates on both ends of the political spectrum. Clients included those running for office at the highest level: Dewey, Eisenhower, Goldwater, Johnson, Kennedy, Roosevelt, Truman, Willkie, and Nixon. Cohen noted in 1964 that selling the various items was no problem, but collecting from the candidates after the election was more difficult, regardless of whether the candidate won or lost (“Apolitical Al Cohen” 1964). This was proven true in 1973 when, despite having close relations to Nixon’s campaign in 1968, Cohen’s company was one of the vendors the 1972 Nixon campaign falsely reported having paid. The campaign treasurer responded that it was a bookkeeping error (Dougherty 1968; “Falsehood Charged” 1973).

Context:

The 1972 presidential cycle was not the first for which Hebrew was used on a presidential campaign button. In 1952, as part of their “everyman” strategy, the Eisenhower campaign circulated buttons with the signature “I Like Ike” slogan in dozens of different languages—including Hebrew. This particular button campaign also included one in Yiddish, a Jewish vernacular that is based on the combination of Hebrew and various European languages but written in Hebrew letters and read right-to-left. This button and a similar one in Yiddish that was produced for the 1900 William Jennings Bryan presidential campaign were most likely directed at Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Between the 1880s and early 1920s, large numbers of Jews immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe, and these buttons targeted them, rather than American-born Jews as a religious community.

The absence of campaign buttons in either Yiddish or Hebrew between 1900 and 1952 reflected the passing of the Yiddish-speaking immigrant generation and the increasing pressures of Americanization on immigrant populations generally. It also may have emerged from an awareness of the dangers of mass-producing campaign materials in a language other than English. The 1900 button misspelled the name of Bryan’s vice-presidential running mate Adlai Stephenson—ironically, the father of Eisenhower’s opponent in 1952—an error that would have been obvious to anyone who knew either Yiddish or Hebrew.

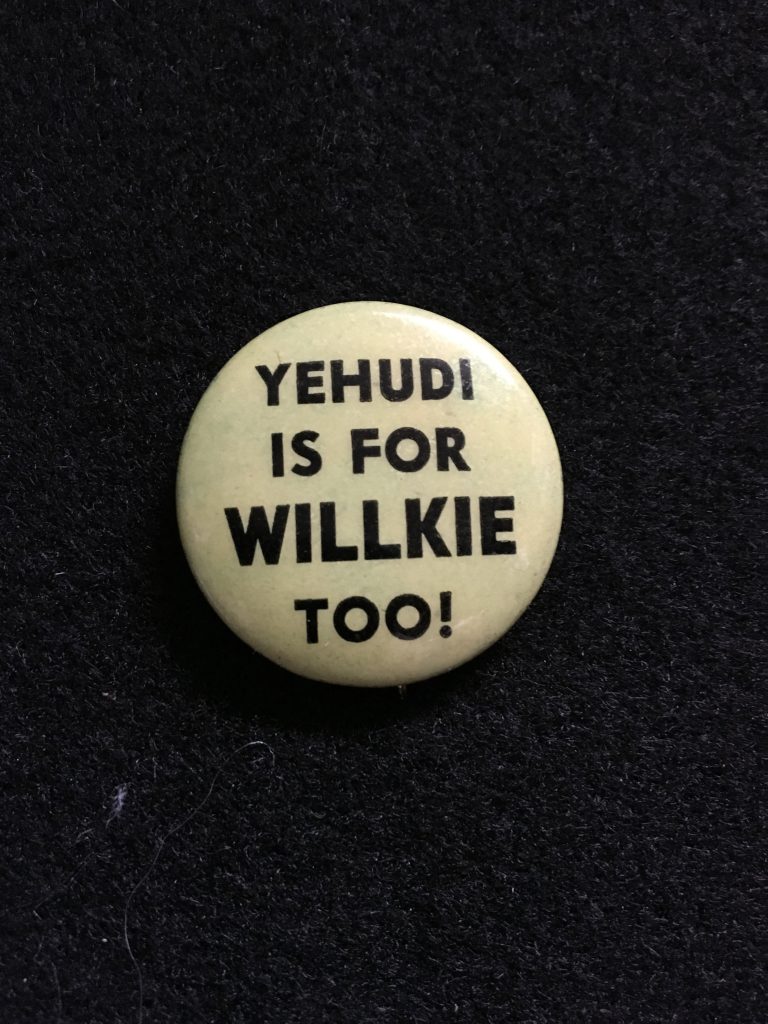

Between 1900 and 1952, buttons aimed at the American Jewish community contained “narrowcast” terms and phrases in English—references that would attract the attention of Jewish voters without drawing the attention of non-Jewish voters. This often was done by referring to a prominent member of the American Jewish community, but also by using “Sefarad,” a Hebrew-looking font that would feel familiar to Jews (see Figures 3, 4).

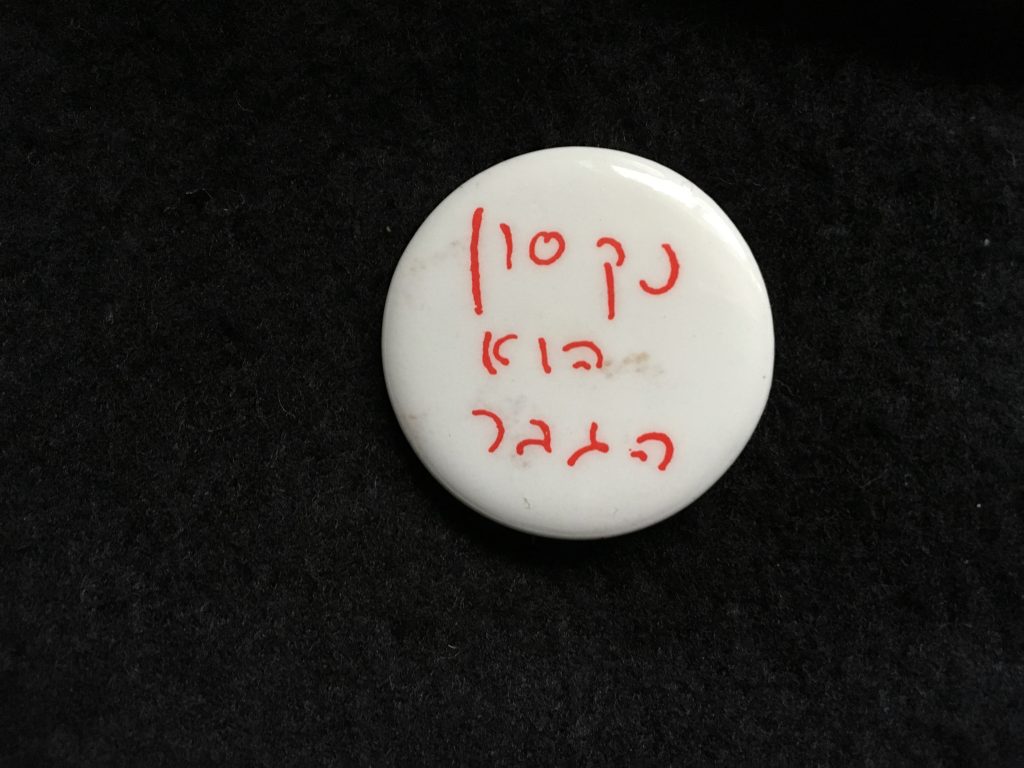

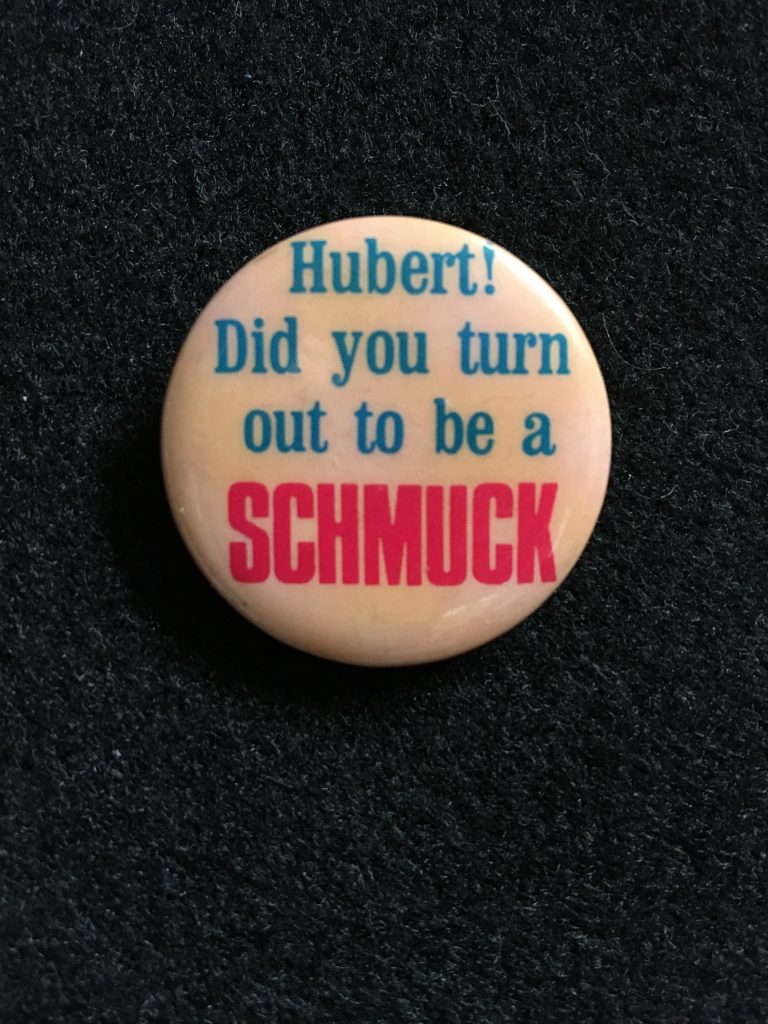

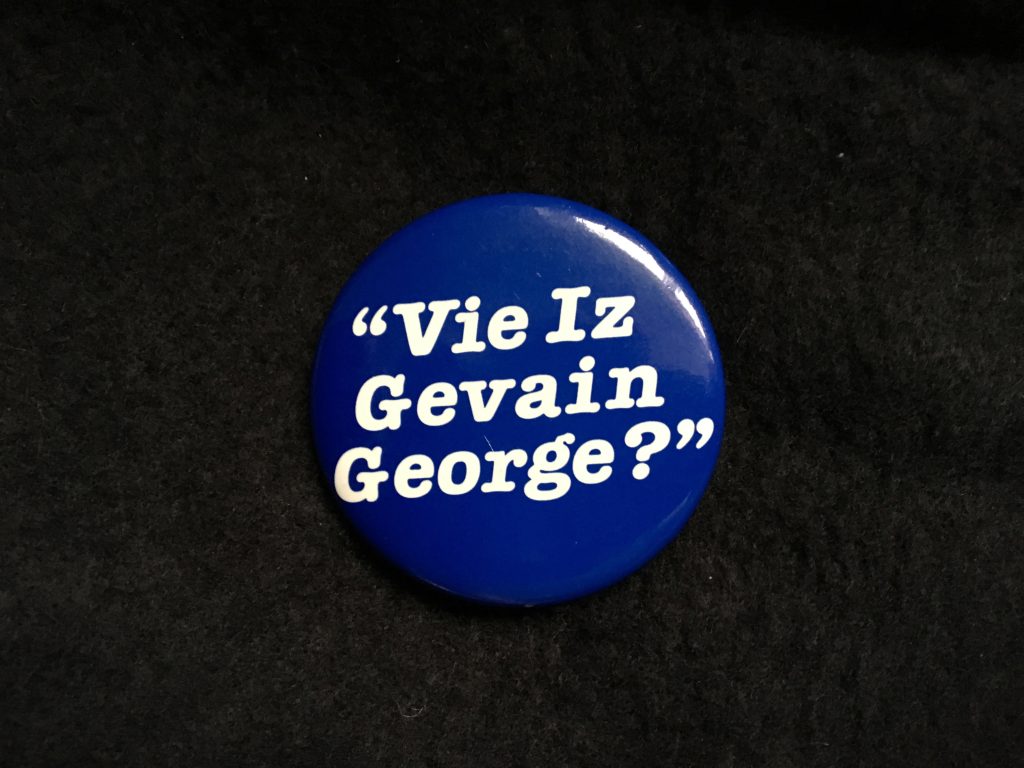

Nixon’s 1968 campaign saw the circulation of a variety of buttons employing Hebrew. One button design (used by both the Nixon/Agnew and Humphrey/Muskie tickets) announced in Hebrew that the wearer was voting for the candidates, with the candidates’ names written in English and their likenesses situated beneath (see Figure 5). Another used a translation of one of the campaign’s slogans (“Nixon’s the one,” in Hebrew rendered as “Nixon’s the man”) but was written informally in Hebrew script, a format that might have limited its reach (see Figure 6). There also were a few buttons using transliterated Yiddish terms (often pejorative) that were increasingly familiar to non-Jews (such as “schmuck” and “nebbish”) (see Figure 7).

In terms of political buttony, the 1972 election cycle was of particular significance because it marked a shift in the representation of Jews and Judaism. From Israel’s stunning victory in the 1967 Six Day War to American swimmer Mark Spitz’s record-breaking seven gold medals in the 1972 Munich Olympics, community self-confidence and the acknowledgment of the Christian dominant culture likely contributed to the rise in American Jewish visibility, even as terrorist attacks on Israeli citizens and Jews worldwide continued.

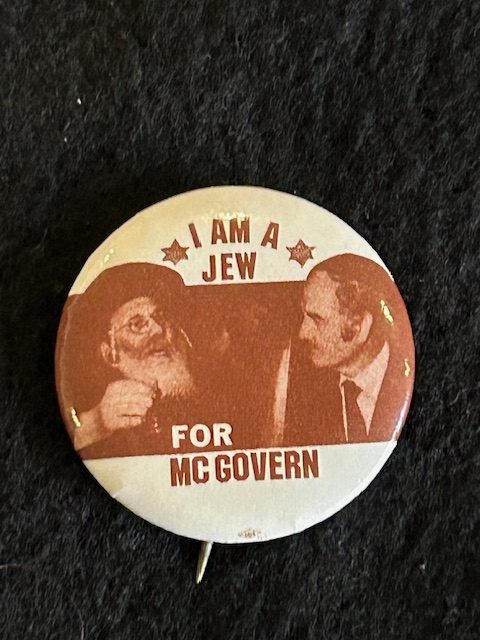

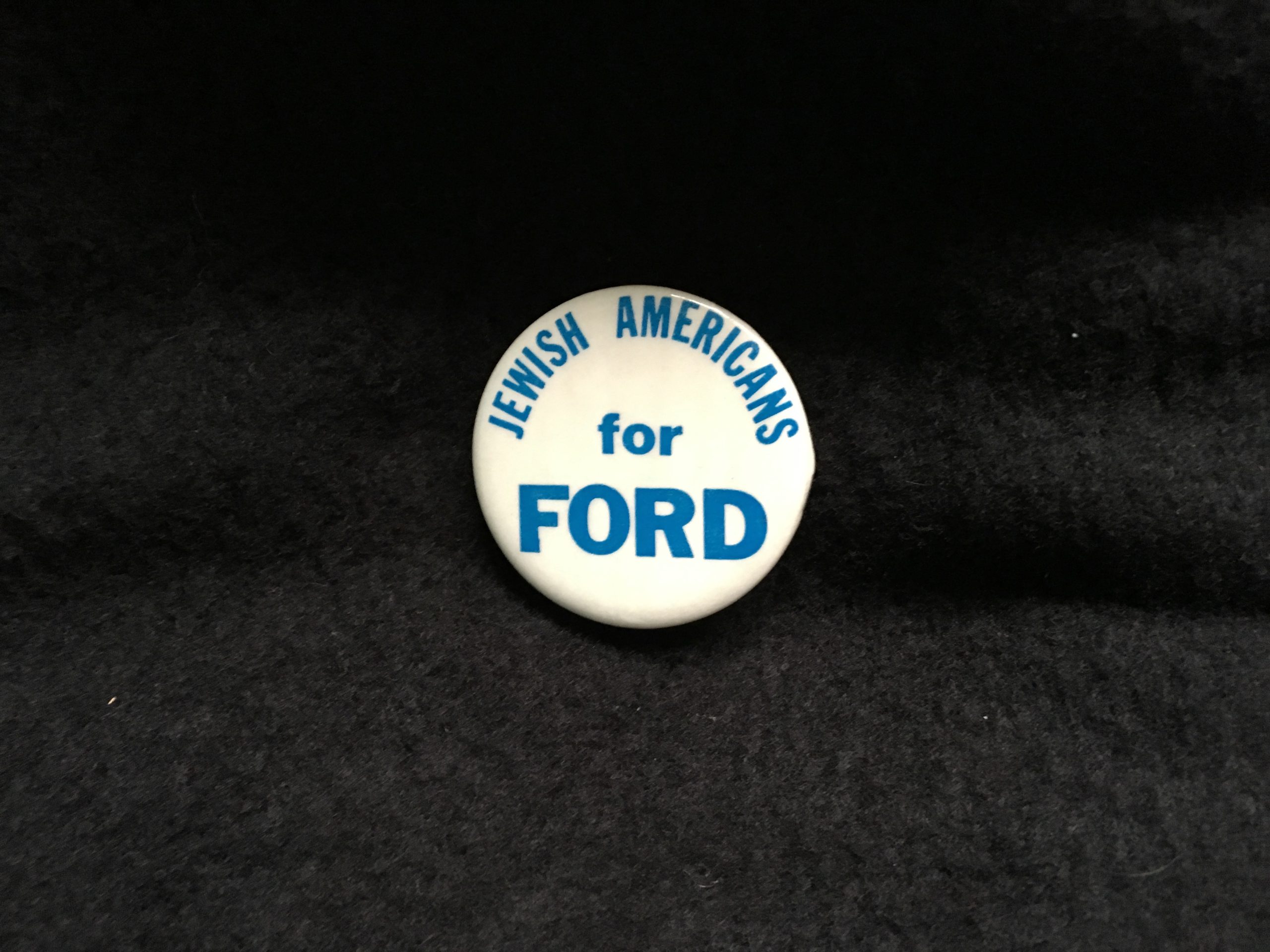

Campaign buttons directed at American Jewish voters got off to a rough start. A 1972 button used a stereotypical image of a Hasidic rabbi to announce that he was “A Jew voting for McGovern” (see Figure 8). Soon, though, presidential campaigns more regularly produced a wider array of button designs that directly courted Jewish voters. These buttons not only used Hebrew and Yiddish (or transliterations thereof), but also direct references to Jewish identity as a positive aspect of voter identification (see Figures 9 and 10).

Creator:

While the manufacturer of the 1972 button is known (and identified on the button itself; see Figure 11), the specific designer is difficult to identify. However, the motivation for this kind of button can be traced back to before the American Civil War. Because the majority of American Jews tended to support the party that represented the least threat to their political security, their party allegiance shifted over time as political positions changed (see Weisberg 2019). Despite their shrinking percentage in the American population (from a high of 5% to a consistent 2%), Jewish voters were an important constituency, partly because of their high voting rate and partly because of their strategic concentration in states with more Electoral College votes. (One scholar later noted that, had the Jewish voters in New York City split more evenly between Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford in 1976, Ford would have carried the state, and with it the presidency; see Sigelman 1991, 188.)

As a result, in almost every presidential election cycle since the beginning of the 20th century, the major political parties have sought the “Jewish vote” as part of their campaign strategy. Post-Civil War Jewish support for the Republican Party was consistent, based on the positive actions taken by Republican presidents and the increasing nativism of the Democratic Party. The Republican shift away from Progressivism in the early decades of the twentieth century, coupled with the rise of left-leaning third party candidates and the coalition politics in the Democratic Party, meant that, between 1928 and 1956, no Republican candidate for President earned more than a third of the votes cast by American Jews. Nixon fared poorly in the 1960 cycle, earning less than 15% of the votes cast by Jews. By contrast, his opponent John Kennedy earned a higher percentage of votes cast by Jews (over 80%) than he did of votes cast by fellow Catholics (Carty 2004, 82). In 1964, Republican Barry Goldwater—the Episcopalian son of a Jewish father—received the lowest percentage of votes cast by Jews for a major party candidate since before 1916, at just over 5%. Nixon’s 1968 campaign did little better, receiving 10% of the votes cast by Jews (see Weisberg 2012, 231).

Nonetheless, Republican candidates continued to court Jewish voters, presuming that Jewish interests would align more consistently with conservative economic policies as the community increasingly moved into the middle class. The overall strategy went better for the Nixon campaign in 1972, when he tripled his previous percentage (to more than 30%, in the higher tier of votes cast by Jews for losing candidates). Republican efforts continued after Nixon, but with similar results. Notably, the one post-War Republican candidate to come closest to parity with a Democratic candidate was Ronald Reagan, whose 1980 campaign circulated a button reminiscent of the 1972 Nixon button (see Figure 12). As with the Nixon campaign, Reagan’s (or any candidate’s) success was not due to a button; it merely reflected campaign aspirations. Reagan benefitted most from the candidacy of independent candidate John Anderson who collected 20% of the votes cast by Jews, many of which likely came from voters who ordinarily would have voted for a Democrat.

By 1972, American Jews were increasingly visible at the highest levels of American politics. The first Jew (and the first woman) to earn an Electoral College vote was vice-presidential candidate Theodora “Toni” Nathan, whose Libertarian ticket received one vote from a “faithless” Elector in Virginia who couldn’t bring himself to vote for Nixon. In the coming years, others pondered (or were seriously considered) as either vice-presidential or presidential candidates. The 2000 election saw not only the first Jew (Joe Lieberman) to be nominated on a major party ticket, but also the introduction of the internet as a serious component of electoral politics.

This, coupled with changes in campaign finance law, not only democratized button design and distribution through design-on-demand Web sites, but also signaled a shifting relationship between fundraising and the bric-a-brac of traditional campaigns (like buttons). By the 2008 election cycle, buttons could no longer be seen as the by-product of a campaign infrastructure, but rather the expressions of Web-savvy designers/merchants, and were catering to all parts of the Jewish—and broader American—political spectrum (see Mazur 2022).

Eric Michael Mazur, Professor of Religious Studies, Gloria and David Furman Endowed Professorship, Virginia Wesleyan University

5 December 2025

Tags: buttons, pinback buttons, presidential campaigns, Eisenhower, Jews, Judaism, Nixon, politics, Reagan

References:

“Apolitical Al Cohen is a Man for All Parties.” 1964. New York Times (May 1): 37.

Carty, Thomas Carty.2004. A Catholic in the White House? Religion, Politics, and John F. Kennedy’s Presidential Campaign. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dougherty, Philip H. 1968. “Advertising: Buttoning Up the Candidates.” New York Times (September 12): 76.

“Falsehood Charged to ’72 Nixon Group.” New York Times (December 12): 55.

Mazur, Eric Michael. 2022. “Strange Bedfellows? Technology, Campaign Finance, and the Marketing of Religion on U.S. Presidential Campaign Buttons.” Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 11:103-138.

Sigelman, Lee. 1991. “Jews and the 1988 Election: More of the Same?” The Bible and the Ballot Box: Religion and Politics in the 1988 Election, ed. James L. Guth and John C. Green, 188-203. Westview Press.

Weisberg, Herbert F. 2012. “Reconsidering Jewish Presidential Voting Statistics.” Contemporary Jewry 32(3): 215-236.

Weisberg, Herbert F. 2019. “The Presidential Voting of American Jews.” American Jewish Year Book 119: 39-90.